homepage & table of contents >> chapter 4

On using the Archival Assemblage: working with artist participants

A brief history of working with other artists

Reinterpretation and remix of content in the archive has been undertaken to test if these processes may actually be methods of preservation that artists can easily and purposefully employ. These are processes that we artists use naturally in our creative practices, but to deliberately and consciously undertake these as creative methods (and document the outcomes), we may then potentially employ all recognised methods of preservation in our creative practices:

- digitisation and storage of content in the archival system;

- migration of media to different formats;

- emulation of obsolescent formats in different media formats and “players”; and

- reinterpretation of the content as new work.

Inviting artist participants to collaborate in the archival space and guests to engage with the archival assemblage through the creative act of remixing content is providing useful feedback not just for testing the system for bugs and errors, but more importantly, for testing the processes required to use the archive and engage with the content. Participants and guests have made some incisive recommendations for the “workflow” of how things are done, and a potential “wish-list” of improvements to the system has been formed. Some of these recommendations are being developed as part of the fourth prototype of the Blackaeonium archival system.

The artist participants, Australian artists Geoff Lowe and Jacqueline Riva (working as “A Constructed World” (ACW)) and Lyndal Jones, have provided additional creative content as case studies that show creative practice alongside the archival act, and the act of collecting/documenting/assembling as a creative practice. Part of the research project included the documentation of the “Explaining Contemporary Art to Live Eels #4” (A Constructed World 2008a) performance and installation work by ACW, and one of Lyndal Jones’ series of feminist performance works, the “At Home Series” (Jones 1977 – 1980).

Working with ACW and Lyndal Jones provided many insights into documentation of variable and ephemeral art works and related creative content. This was useful for the research, to test the documentation of different kinds of artwork. Where these two archival projects were less successful, was in how much the artists themselves could engage with archival acts on a day-to-day basis. The ACW project in particular had the least success in artist participation due partly to the “tyranny of distance” (artists living and working in Europe), and partly to that resistance to archiving: despite seeing the need for archiving our creative content, and being interested in the methods and processes, when it came to putting in the hours, they just simply didn’t have the time.

The At Home series is more successful as an example of artist participation. Jones acted as a director of the project - as she does with her own art projects. The digitisation of content and the archival work was done under Jones' direction. This project is more complete and the archive continues to be used to remix content and create recombinant groupings of content in the archive. It's principal contribution is that it has been physically exhibited in the exhibition “A Different Temporality: Aspects of Australian Feminist Art Practice 1975-1985”, a significant exhibition of Australian feminist art from 1975 – 1985 (McFarlane 2011) allowing the work to be viewed by a large public audience.

Jones as the central artist for this archival project, has had input into certain interface designs and updates made to the Blackaeonium archival system to improve user engagement, and has undertaken her own remixes of the creative content in the archival assemblage. The system will continue to be an active creative space over time.

The tensions in engaging artists in archival space became evident with the first two artist-participant projects. This was the main impetus for initiating the Atemporal collaborative project (Cianci 2012a). Individuals I invited to this project (some artists, others different creative practitioners) were excited by the idea of creating and documenting in a shared archival space, and are undertaking all of the documentation themselves. This group are interested in the possibilities for remixing and curation of work in our overlapping archival assemblages – and there are some collaborative outcomes that are beginning to appear at this early stage (as will be discussed).

The Guest Remixes project in the Blackaeonium archival system was also initiated to challenge standard notions of user experience with websites. Undertaking this research as a creative endeavour, the outcomes require testing as a creative endeavour. Standard user testing methods for websites (undertaken earlier in the research) were not very useful for developing the creative aspects of the project, nor for providing the types of information required to test engagement with the content and the archival assemblage overall.

Documenting the work of artist participants and collaboration with artist and audience participants was an important part of the research for testing the theories and methods developed during the project. The project outcomes have added to the investigation of the research questions in a very direct way. The outcomes have challenged the notion of what the archive can hold, the creative possibilities to be found within it, and what meaning can be derived from it for artists and other interested stakeholders.

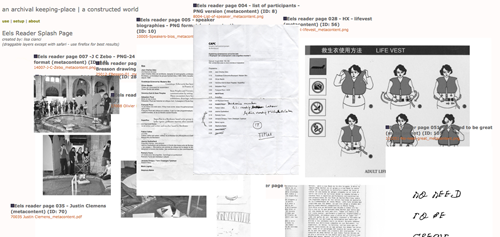

A Constructed World – Explaining Contemporary Art to Live Eels #4

Geoff Lowe and Jacqueline Riva are two Australian artists currently residing in France. They collaborate as A Constructed World (ACW) and have many online presences documenting installations, publications and performance works stretching back to 1997, and covering many locations in Europe, Australia and the USA.

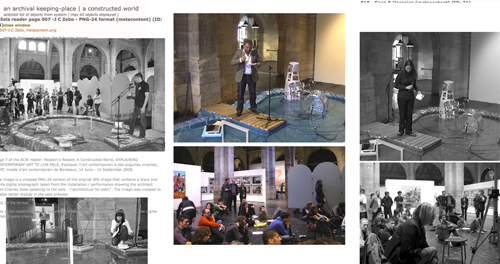

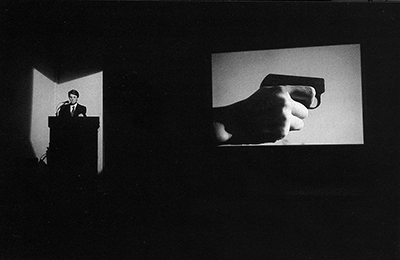

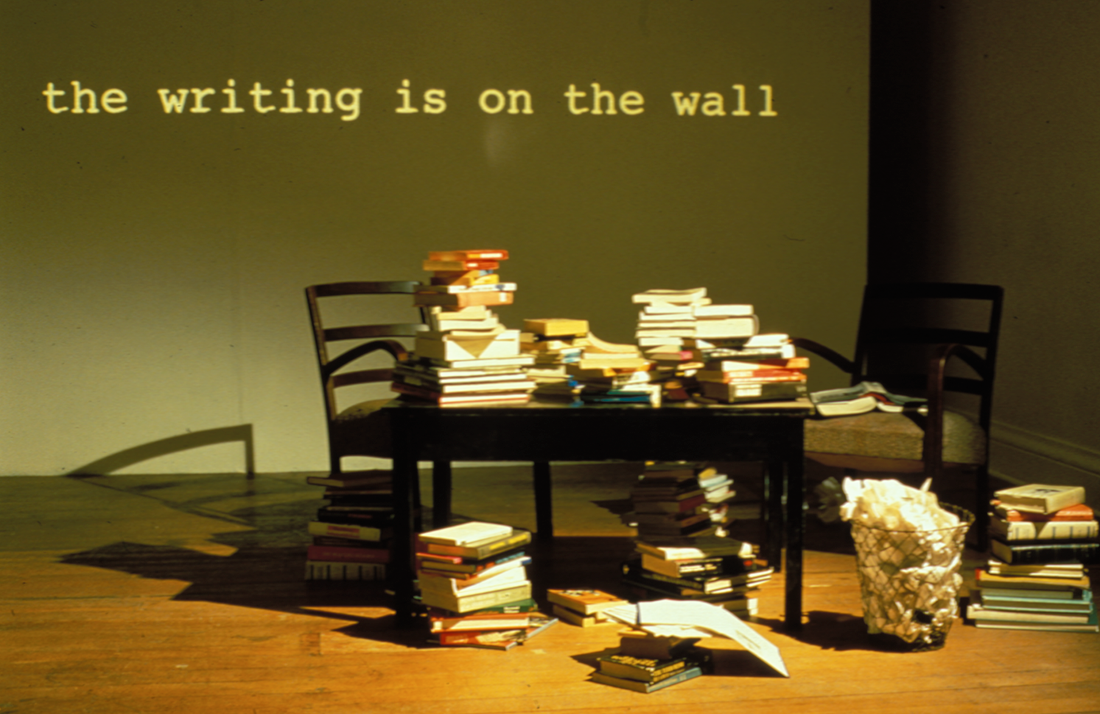

Figure 4.01 ACW, Explaining Contemporary Art to Live Eels #4 (A Constructed World 2008a)

(image with permission from ACW)

(click to view larger image)

In the work of A Constructed World, one finds oneself to be part of a large group, one discusses a great deal, becomes bored, sometimes runs nude in the forest, sings badly, dines well, dances, acts foolish, encounters strange beasts, creates things there. Rarely has an oeuvre such as that of the Australian duo better put into practice that precept which Allan Kaprow already formulated 45 years ago with regard to the happening: the transforming of art into permanent event, a space which is open to contingency, to encounters and to experimentation. With ACW one is never sure when the work begins and whether it has finished, and those who approach it take the risk of finding themselves to be an integral part of the creative process. (Laubard 2004)

ACW describe their work as “not-knowing-as-a-shared-space”. The works they create include performance and installation, publications, seminars, forums, events, and exhibitions. ACW works are diverse in nature. For example: Hobbes Opera Part 1 (A Constructed World 2008b) involves a performance using a custom-built, multi-player electric guitar with six necks. The “guest” participants play The White Stripes’ song “Seven Nation Army”. The event culminates with the destruction of the guitar – two participants cut it to pieces with an electric saw. Another of many examples using participants is the Melbourne Choir of Complaints [1](A Constructed World 2007a),where the non-professional participants literally sing a “litany of complaints” in a public performance. Other works such as – Errors, Deceits, Mistakes (A Constructed World 2006), involve publication in hard-copy format of “Readers” that include texts by ACW, texts by other authors about ACW, texts on related themes, images of performances/events, or related imagery collected for use in installations/publications. These Readers often accompany events and installations, or may be stand-alone publications.

Figure 4.02 “Seven Nation Army”, Hobbs Opera Part 1, at CACP Museum Bordeaux, from the year long project Saisons Increase

(A Constructed World 2008b), <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xpy2JmiVAq4>

Figure 4.03 errors, deceits, mistakes n°1, édité par costractedworld 2006, centre national de l'édition et de l'art imprimé, (cneai), France (A Constructed World 2006),<http://errorsdeceits.blogspot.com.au/>

(images with permission from ACW)

(click to view larger images)

ACW projects use creative practice to create a discourse on ideas relating to collaboration and participation, and they incorporate elements such as performance, installation, and physical media including human (and sometimes eel) participants in their artworks. They reference theorists and philosophers, writers and artists such as Sigmund Freud, Giorgio Agamben, Joseph Beuys and Marcel Broodthayers[2].

Aligning themselves with the ideas of Joseph Beuys, ACW do not see communication occurring as a one-way flow. In their collaborative works, they make it explicit that communication is a reciprocal process between the artist and the viewer, the participant and the artist (Uran 2007)ACW have a peripatetic creative practice that means they have lived and worked in several cities around the world, and have a substantial body of artworks exhibited in prominent international galleries and contemporary art spaces.

Research, listening, inclusion, incorporation, interrogation, information gathering are represented in ‘evental sites’ that could be called platforms. These platforms create, represent, make present, recover and picture momentary and ongoing interfaces with audiences and generate audience performances. (A Constructed World 2007b)

Figure 4.04 ACW - from the “Eels #4 Reader”, images of participants as viewed in the Blackaeonium archival system

(ACW 2009a)(image with permission from ACW)

(click to view larger image)

The content created by ACW is temporal, ephemeral, and contains multiplicities and recursive elements that were well suited to this research: for example, imagery and artefacts are reused in multiple performances, and in hard copy/website publications. The intention was to experiment with diverse and ephemeral art forms that would challenge the concepts and theories proposed for working creatively within an archival continuum framework.

This phase of the research in 2009 began with documenting a selection of ACW project work, in particular looking at different ways of capturing the variable and complex nature of their work in a digital system.

ACW agreed to participate in this research by allowing the archival documentation of material relating to the project “Explaining Contemporary Art to Live Eels #4” (A Constructed World 2008a) using an iteration of the Blackaeonium archival system created for this discrete collection (A Constructed World 2009a). The “Eels #4” project contained live eels in a tank, installed within the exhibition space at CAPC, Bordeaux. The performance event involved guest participants “explaining contemporary art” to the eels. Microphones were set up in the space, to be amplified into the eels’ tank, and the participants read selected material (either their own statements, or texts by other authors) into the microphones. Other participants (Veronica Kent and Sean Peoples) chose to send their messages telepathically to the eels.

Figure 4.05 Freud’s drawings of eels – from the ACW archive (ACW 2009a)

(image with permission from ACW)

(click to view larger image)

This work by ACW has a conceptual basis with two major influences: Sigmund Freud’s early work in 1873 at the Austrian zoological research station in Trieste, dissecting hundreds of eels in an attempt to discover the male sex organs (Freud, Boehlich 1990) – the life cycle of eels was unknown at that time; and one of Joseph Beuys' most famous performances titled “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare” (Beuys 1965)[3] in which he covered his head in honey, his face in gold leaf, and sat in a chair in the corner of the gallery, lovingly cradling a dead hare while whispering to it, describing artworks on the gallery walls.

As with other ACW events, video, image and artefacts from the performance and installation were collected for a “Reader” publication. The material assembled into the “Eels #4 Reader” (A Constructed World 2008a) was an ideal case study of material to archive in the Blackaeonium archival system as it contained content and documentation of the performance already in digital format. It was useful to document the diverse, ephemeral and distributed nature of the content in ACW projects, their own relationship to archival theory and discourse relating to the archive, the use of participants and contributors in the installation and performance works, and the granularity of the archival documentation of their work.

This archival work conducted with the “Eels #4 Reader” material tested the system and methods of documentation. It was the first opportunity to document work other than my own and as such, many issues relating to preservation, the archival act and the creative act arose during the documentation. It was possible to improve many areas of documentation practice and consider important elements that did not factor into my own work at that time, such as the use of participants in performed works, and the use of reproduced material not created by the artists.

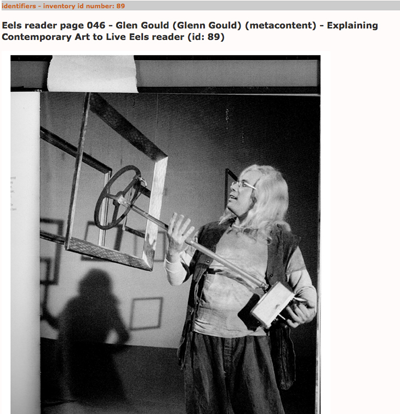

Figures 4.06 & 4.07 Images from the ACW archive (ACW 2009a) showing images of Glenn Gould, and Salvador Dali and Gala (part of the Explaining Contemporary Art to Live Eels #4 publication)

(images with permission from ACW)

(click to view larger images)

I relied on my own research to gain further information about some of the material used in the “Eels #4 Reader” (A Constructed World 2008a), where the origin of material was uncertain, to establish the exact provenance of content that was used. Certain objects from the “Reader” (Figures 4.06 & 4.07) such as an image of Salvador Dali and Gala, and an image of Glenn Gould in costume – which were not part of the “Eels #4” installation and performance event, lacked information which was necessary for the Inventory level documentation[4]. This additional information was included in the archival documentation to provide metadata and contextual information for the content and therefore, for the artwork.

Artwork that uses mixed media in this way is problematic from an archival perspective. ACW uses imagery in their “Eels #4 Reader” publication that relates to or makes comment on their performance and collaborative work. Some of the content used in the “Eels #4 Reader” was not created by ACW, but appropriated for use in the Reader. The imagery has been captured from printed publications and digital video footage made from an analogue video (available on a website) of a television show. This kind of reinterpretation, migration and Remix (Navas 2011a) in their work requires decision making regarding the level of archival documentation required, and also identification of what exactly is being documented.

Figure 4.08 ACW, Explaining Contemporary Art to Live Eels #4, screen capture from the archive

(image with permission from ACW)

(click to view larger image)

Similar situations arose with other elements in the “Eels #4 Reader”, such as diagrams of Chinese seat belt fastening instructions (visible in Figure 4.08) appropriated for the performance by a participant.

Other instances in the “Eels #4 Reader” involve the participants reading the work of other authors (for example, participant Lydie Vignau reads Michel de Certeau [5]). The concept of provenance, chain of custody, creation and use, and possibly rights management are obvious issues challenged by artworks such as this. All available information on participants in the performance and Reader, and content used in the performance and Reader were documented in the Blackaeonium archival system, and names of participants or indirect creators of content included in the inventory descriptions and tag cloud. This level of granularity is important to document because it relates to the creative intent of ACW where general audience participation or selected individuals participating in the event (inclusion) is crucial to their work.

The whole question of the archive is of course vexed. We make works to address what eludes us. You can, in a sense, archive a life but if that makes the immediate or unmediated response of the viewer irrelevant then something important is lost. Saving too much creates a loss, or restricts the audience, because it suggests there will eventually be a singular ‘knowing’ reading. I guess we are waiting to see what our work means. (A Constructed World & Budney 2007, p. 130)

Through this work with artist participants, it became obvious that the Blackaeonium archival system would require some modifications in the next prototype version to be developed, as no distinct field for participants was included in the second prototype. The interpretation of Dublin Core Fields (Dublin Core 2005) used for the second prototype of the Blackaeonium archival system had not included distinct fields for participants - called “Contributors”[6] in Dublin Core elements - nor for “Coverage”[7] or “Language” (although there is a Location field which could be repurposed for “Coverage” rather than for location of the resource if not linked to the object in the system)[8].

The “Eels #4 Reader” documentation challenged the system in a number of ways, and except for the case of “Contributors”, “Language” and “Coverage” fields, it proved to be more than adequate for documentation of complex work of this nature. It also tested the technical aspects of the system - few bugs were detected in the PHP/MySQL code. Adding fields or repurposing existing fields that are not used as anticipated such as Operating System and Hardware was not be difficult and did not require substantial change to the overall design of the system.

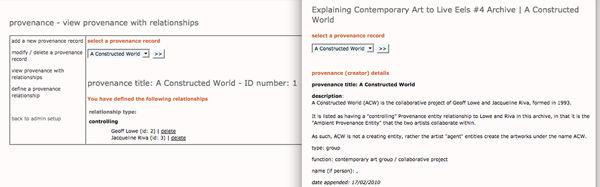

Figure 4.09 Screen Capture from ACW Archive showing example of Provenance entity relationships

(click to view larger image)

The nature of ACW as a collaborative group enabled testing of the structure of the Blackaeonium archival system database. In particular, the ability to document Provenance entities and relationships was determined to work for this project where the “ambient” Provenance entity “A Constructed World”, was established and the related artist “agents” (Lowe and Riva) that create the artworks, were then created and linked to the ambient ACW Provenance entity, and these entities all linked to the objects in the archive.

The archiving of the “Eels #4 Reader” materials provided a basis that was improved in the second phase of the research involving participating artists – the archiving of Lyndal Jones' "At Home Series".

Lyndal Jones – The At Home Series

I also work to represent art as process, not product; the artist as worker, not revered individual; the ephemeral/memory as substantial and important; the different disciplines as series of intersecting conventions, not fixed, discrete entities – all in opposition to the representation of art as commodity.

These representations all exist through media, materials, environment, mode of production that are themselves meaning-producing, not neutral vessels of communication. My intention is always to reveal this lack of neutrality.(Jones c. 1978)

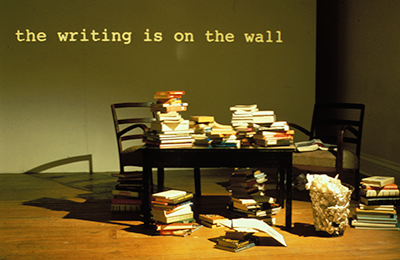

Figure 4.10 Lyndal Jones, At Home: Ladies a Plate 1979, photograph by John Dunkley-Smith

(image with permission from Lyndal Jones)

(click to view larger image)Lyndal Jones is an Australian artist, academic and Supervisor for this PhD research project. Jones’ vast body of work spanning a number of years, her creative practice, her understanding of the archive and the ability for her to provide a substantial series of variable media artworks (and an exhibition context for the outcomes of this phase of the research) made her an obvious choice for inclusion as an artist participant in this research project[9].

She has produced many diverse art projects since her first gallery exhibition the late 1970s. Her work has been shown internationally at such high profile locations as the 49th Venice Biennale, “Deep Water/Aqua Profunda” (Jones 2001), and in major contemporary art spaces such as the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (Melbourne), Museum of Contemporary Art (Sydney) and a host of international galleries, museums and universities (Engberg et al. 2008). She has written for influential Australian feminist journal LIP (and was a LIP board member in the early 1980s), among other published texts, and is currently a Professor in the School of Media and Communication at RMIT University.

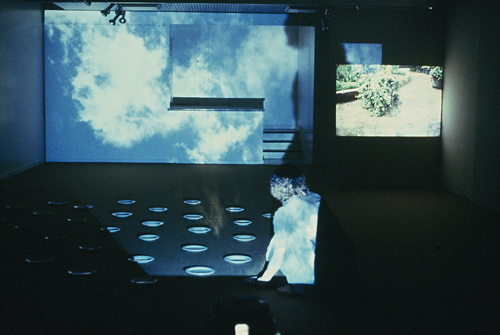

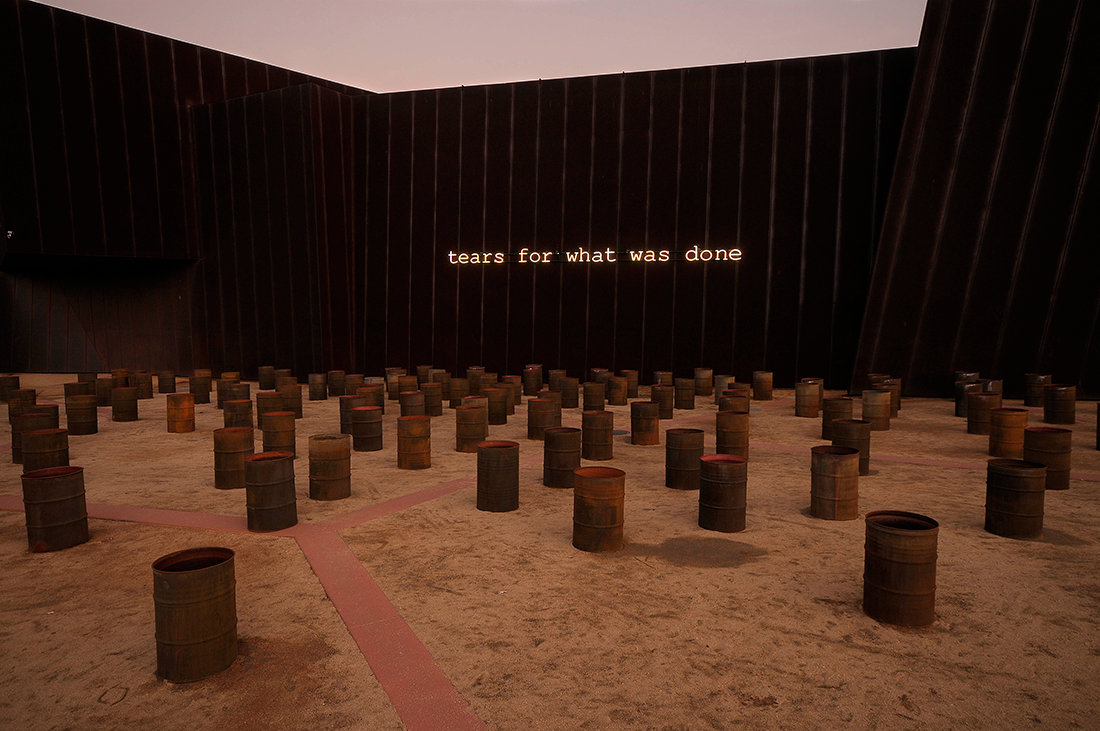

Figures 4.11 & 4.12 "Room with Finches" 1994 / 2008 and "Tears for what was done" 2008, images from Lyndal Jones' survey exhibition at ACCA titled "Darwin with Tears" 2008.

Photographs by John Brash, images with permission from Lyndal Jones

(click to view larger images)

Jones’ works often involve performance and/or installations on a large scale, or works undertaken as research projects over a number of years. These works include the use of mixed media, video, light displays, and sometimes human and animal participants. Examples include works such as: “Room with Finches” (Jones 1994/2008), which involves an aviary installed in the exhibition space filled with live finches and video projection; “Tears for what was done”(Jones 2008) an installation using drums filled with water and neon light; and “Crying Man 1” (Jones 2003), a video installation that requires user interaction within the installation space to trigger different video responses[10].

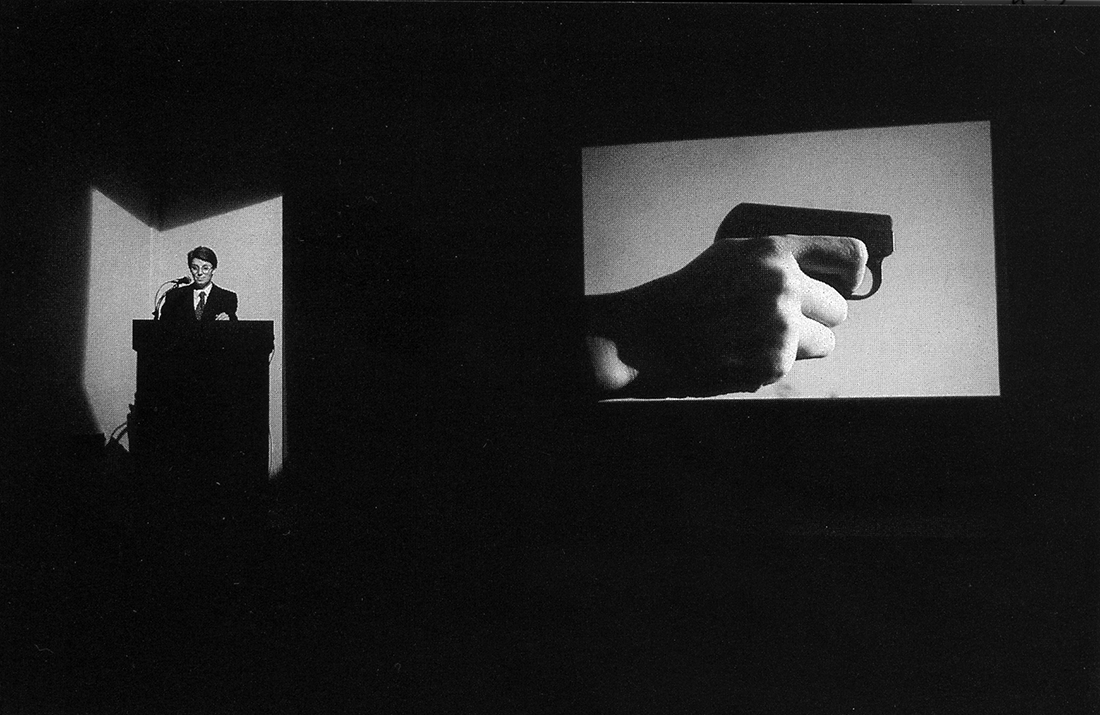

Figures 4.13 & 4.14 Prediction Pieces 6 & 7, Lyndal Jones 1986,1988

Photographs by Sandy Edwards, images with permission from Lyndal Jones

(click to view larger images)

Lyndal Jones’ work “The Prediction Pieces” (1981 – 1991) (Cramer & Jones 1992), a long-term project which involved creating ten performance works over ten years (using slide projection, performance, text, audio and video), already exists as a reinterpreted archival work held in The Contemporary Art Archive at The Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney (2012) as previously discussed in Chapter 1.

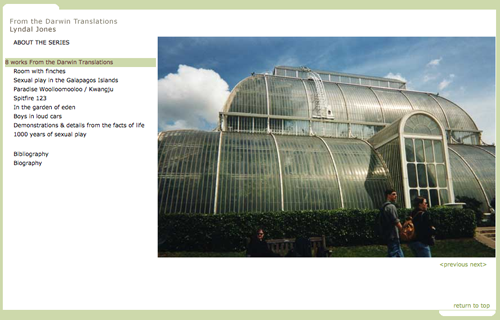

Figure 4.15 Image captured from Lyndal Jones’ PhD website – From The Darwin Translations, (Jones 2005)

<http://avocaproject.org/DarwinTranslations/index.html>

(image with permission from Lyndal Jones)

(click to view larger image)

Jones completed her PhD in 2005 “on the propositional nature of art research and use of the web to archive complex, time-based artworks” (Jones 2005).

While it could be said that every artist has an archive of their work comprising their notebooks, sketches, objects and artefacts collected in odd corners of their home and studio (making storage a perpetual concern), there is only a small history of artists who have compiled their own archives which have become, as a result, artworks in their own right.

This practice suggests an artist who regards his or her individual works to be part of an overarching project and who then takes the opportunity to construct another, bigger work by bringing the individual elements together. (Jones 2005)

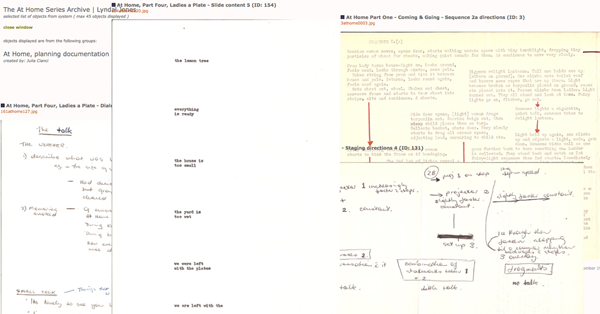

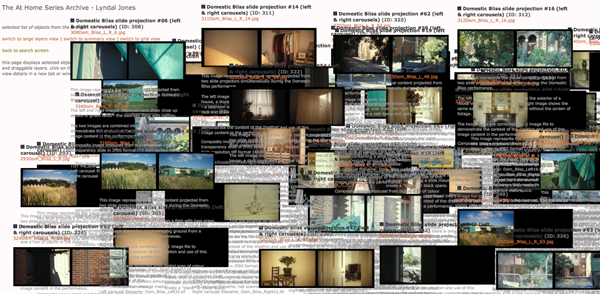

Figure 4.16 The At Home Series Archive, screen capture from the Blackaeonium archival system, Lyndal Jones

(image with permission from Lyndal Jones)

(click to view larger image)

As with the work of ACW, the variable nature of the “At Home Series” makes it ideal as a case study in working creatively with the archival continuum. Although it is a series of 5 performance works from 1977 – 1981, it was an appropriate selection for archival documentation and for testing the methods and processes developed through this research. The performances involved slide projection, audio playback, storytelling, actions in a physical space, props and in the case of the first performance “At Home: Coming and Going”, participants.

My art practice focuses […] on representation itself, working to render visible supposed cultural ‘truths’ through the presentation of alternatives.

I work to challenge the constraints of a patriarchal control of language by representing woman as subject – denying determination by the viewer as completed, single entity (object) – and able to manipulate materials, images and ideas. That is, to act, to have power. To this end, I also focus on the use of many languages (physical, sensory, as well as verbal).

(Lyndal Jones, from her Artist Statement (Jones c.1978))

Figure 4.17 Sample of documentation from the At Home Series Archive, Lyndal Jones

(image with permission from Lyndal Jones)

(click to view larger image)Thirty years has passed between the performance events and the archival documentation and accession into the online, digital archive of the remaining records and artefacts. Despite this, the archival material is extensive, well maintained and resonant for new audiences. For example, there are hand written notes mapping out the “score” or “script” of a performance which can then be viewed next to notes about the stories that will be told, and the slides used alongside the physical actions and narratives in Jones’ performance (see Figure 4.17). The collection contains hand written notes and workbooks, typewritten pages of texts used to plan the performances and installations, audio reels and cassettes, photographs, publications, ephemera relating to the promotion of the performance events, and a large quantity of slides – most of which were used in the performances, but some of which were photographed documentation of the performances.

The planning documentation (paper documents, ephemera and workbooks) adds a great quantity and quality of contextual information to support the artefacts (slides, audio and photographs of the performance). There is great potential for tiering with this archival collection. There is the possibility for future curation of the archival collection or subsets of the collection as exhibitions both online and in physical space, and as printed or online publications using selected content in the collection. Hosting the archival documentation of the "At Home" series in a digital archival system will be able to continue to facilitate a wide range of creative outcomes.

This archival project is not useful simply as a finding aid, it is a documentation, a reinterpretation and an online publication – it gives access to a wide number of users, and is useful to the artist in creating recombinant new works or new experiences of the original work.

Jones sets up a situation of simultaneous information systems, relaying a set of variations on the thematic material of a voyage. A series of slides detailing familiar sights of travel are projected: short narratives are read by the artist at intervals is played, the artist enacts tasks relating to travel (packing, carrying suitcases, etc.): these systems appear in a variety of conjunctions and disjunctions, generating a multiplicity of interrelations and interpretation. (Chin 1980)

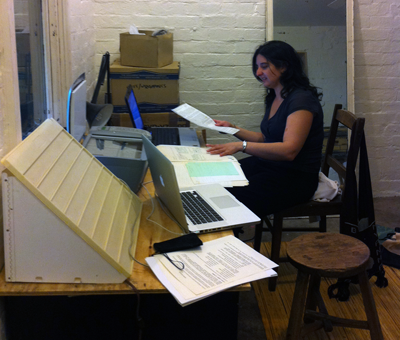

Figures 4.18 – 4.22 Images of the physical archives and the archival documentation project

showing Julia Cianci and Lisa Cianci on-site digitising the hard-copy paper archives.

(click to view larger images)

This phase of the research directly addresses the idea of the archival act as a creative one and the artist as archivist and self-documenter. These records and artefacts not only represent the performances and materials used in the performances such as slides, but they show process and development of ideas and content for the works, and commentary about the works – metacontent and documentation that is vital to gaining a meaningful understanding of these artworks and the context of their creation and presentation to an audience. The research project adds value to the archival collection because it creates (as remix and reinterpretation) the means for providing access to materials relating to works that are quickly becoming inaccessible. For example, slide projectors and reel-tape audio players are increasingly difficult to source. Digital versions of these artefacts presented in the online archive provide ready access and allow for the control and management of the content (both analogue and digital content).

This project demonstrates what can be presented or re-presented with an artist’s archives, how the archive can be used to keep artwork current in the continuum, to create multiplicities and proliferate the work and the ideas behind the work through an ambient framework (the online, digital archival space).

Figure 4.23 Lyndal Jones, At Home: Domestic Bliss - low-resolution image compiled from two high-resolution images for the online archive

<http://athome.blackaeonium.net//access/invviewpopup.php?itemid=307>

(image with permission from Lyndal Jones)

(click to view larger images)

There were many archival and creative issues to deal with in undertaking this documentation. Artist Dean Keep (Keep 2006) scanned most of the large quantity of slides that form a substantial part of the archival collection. Keep worked with Jones to determine how the slides should be scanned in accordance with Jones’ artistic intent – how she wanted them to look in terms of colour, resolution and quality. The quality and colour of the slides is extremely good but there are properties and settings that will determine how the scanner interprets the pixels it collects from the slide scanning process. Having an experienced visual artist to do this digitisation work was crucial to the quality of the end result. The high quality of digital reproductions of the slides from the collection adds to the aesthetic quality of the archival assemblage.

We also had an archival assistant to document a large portion of the archival objects at the Inventory level for the “At Home Series”[11]. Another archivist to work on the archival documentation as a professionally trained user was of benefit, to test the archival system at a high level and provide a critique of usability and functionality. This enabled a more rigorous analysis of the Blackaeonium archival system, with useful recommendations for areas that could be improved or added to. Some minor changes were made whilst the documentation work was underway – based on user requirements at the time.

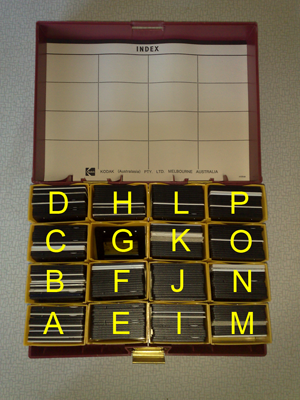

Figure 4.24 On The Road Again: A performance by Lyndal Jones. A Kodak Carousel Diamagazin loaded with 80 slides (photograph by Dean Keep)

Figure 4.25 At Home, At Home, Lyndal Jones Boxed Slides (photograph by Dean Keep)

(images with permission from Lyndal Jones)

(click to view larger images)

The only slides that were not scanned were ones containing foil inserts. These inserts create “blanks” – blocking light from the slide projector to leave a dark space in the sequence of projection to create the appropriate rhythm for the projected slide show, in order that Jones could play the slide carousels automatically while she performed along side them. As such, there are some spaces in the sequence of slides scanned and digitised. This loss of information is not total as the analogue artefact does exist, but there are some gaps in the digital documentation.

This is not unusual for an archival collection, but through the metacontent and archival documentation including contextual information, (such as series descriptions) it is possible to gain an understanding of this performance work and how the visual content was displayed (including the blanks), and to create different recombinant presentations of the content through the archival system’s interfaces. There are possibilities for further reinterpretations of the slides, such as recreating the timing of the slide show by placing the sequence of images and blanks into a video file to show how the slides would have played in the performance events.

The high-resolution images scanned by Keep were too large to upload to the online archival system, and are too large to view in a browser window. The decision to scan at high resolution was made firstly to capture as much information from the slide as possible, and secondly to allow for potential high quality reproduction as printed media or to other formats. Some of these were used in the MUMA exhibition.

Lower resolution images suitable for the web browser, were uploaded to the Blackaeonium archival system with their attendant documentation, and then these objects were linked to the high-resolution images by listing file names and location on storage media. Users engaging with the slides from the archival collection in the online system are able to download low-res content quickly as a reference copy, but the artist’s intellectual property is protected to some extent by restricting access to the high-resolution image, thus preventing quality printing or publication. On her PhD From the Darwin Translations:

So, in all its fragility, but with its extraordinary power to communicate to vast numbers of people, I have selected the Web as the site for this archive of From the Darwin Translations […] I am not, however, wishing to abandon copyright. Images from this series can, of course, be down-loaded. However, they are very low resolution. And the video clips shown are small sections or low resolution of the works themselves. More important than copyright to me however, is the maintenance of some control on the quality of the physical experience of engaging with the artworks I make in the context of their development and exhibition.

(Jones 2005)At present the entire archival system (except for five images on the homepage interface) for the At Home series are closed to general public access. In the MUMA exhibition, a guest login was used to allow gallery visitors to access all aspects of the archive in a restricted setting, but Jones has determined, that at least for the short-term, the archive will be accessible to “guest” users only due to her intent to control “the quality of the physical experiences of engaging with the artworks”, Jones can select how, when and where the content will be made available.

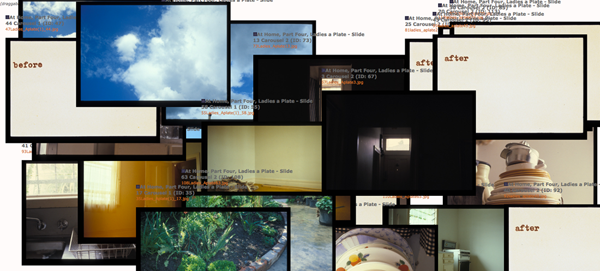

Figure 4.26 Image from Lyndal Jones’ At Home archive showing a series of digitised slides from the collection

(image with permission from Lyndal Jones)

(click to view larger image)

There were other issues in dealing with the slides used in the performances: the “At Home: Domestic Bliss” performance (1980) involved two slide projectors simultaneously projecting sequences of images that were shown together while Jones told stories relating to the images. These slides have been scanned separately – as they are discrete items in the archival collection, but Jones requested that in the online archive, the images that were projected together always be viewed together otherwise the context and meaning of the performance or aspects of the performance may not be correctly understood.

This relates directly to issues of intent, granularity (what level to document and in how much detail) and what exactly is being archived. The content may require reinterpretation, may be disembodied from the format to provide the best means of engaging with the work long after the performance has finished. The decision was made to combine the images from the two corresponding slides into one low-resolution image for the web browser. These “double-images” (Figure 4.23 & Figure 4.26) are then uploaded to the system as single objects, each documented as one object, but linked to the two high-resolution scanned images of the slides. Thus no matter which interface is used to view the work, the user can always see the images, as they would have been shown in the performance.

Figure 4.27 Lyndal Jones, At Home: Coming and Going 1977, photograph by John Dunkley-Smith

(image with permission from Lyndal Jones)

(click to view larger image)

Overall, the Blackaeonium archival system performed well in documenting all aspects of the At Home series. In particular, the functionality of the “Add new object from existing object” Inventory data entry form, which enables the user to use one object’s documentation as a template for another object enabled a rapid documentation of content such as the slides series where format and contextual information is the same for all items in the series. The main fields to contain unique information where the slides are concerned are generally the title, descriptionContent and filename, thus data entry work was minimalised.

Figures 4.28 & 4.29 Screen captures of the At Home series archive showing audio content in Grid and Layer interfaces

(image with permission from Lyndal Jones)

(click to view larger images)

Amongst the “At Home Series” collection are audiotapes and audio cassettes that contain tracks used in the “At Home, On the Road” 1979 and 1980 performances. The digitisation of this material encountered similar issues to the scanning of slides. High quality audio has been digitally recorded from these analogue media objects. Low quality MP3 versions of portions of the audio have been generated from the high quality files and uploaded to the Blackaeonium archival system. In the same way, a user may rapidly download audio content along with other media, but will not have access to the high quality audio files. The audio provides an additional dimension to enable engagement with the content.

Placing text, image and audio together in a webpage interface does not emulate the original work. It is an interpretation and a representation of the remaining artefacts. This archival resource may not be considered preservation of the artworks as originally intended to be presented to an audience - the artworks were performances executed at particular times in particular locations. It does, however, preserve ideas and concepts that are important to our cultural history. This addresses previously cited questions regarding the personal archive by McKemmish and Upward, in particular: “bearing witness to the cultural moment”; and “postcustodial archival regimes that can ensure that a personal archive of value to society becomes an accessible part of the collective memory” (McKemmish & Upward 2001). This work by Lyndal Jones captures the zeitgeist from that time and place – the contemporary art scene and the feminist discourse that was active in Melbourne in the late 1970s and early 1980s. As a result of undertaking this work, it became clear that the Blackaeonium archival system is assisting in the preservation of that cultural memory and making the work available in a meaningful way, to a greater audience.

Performance is […] characterised by the play that the artist makes between […] elements: the ways in which relationships are created and the values that are implicit in attitudes to the elements and the relationships created between them (Jones 1992)

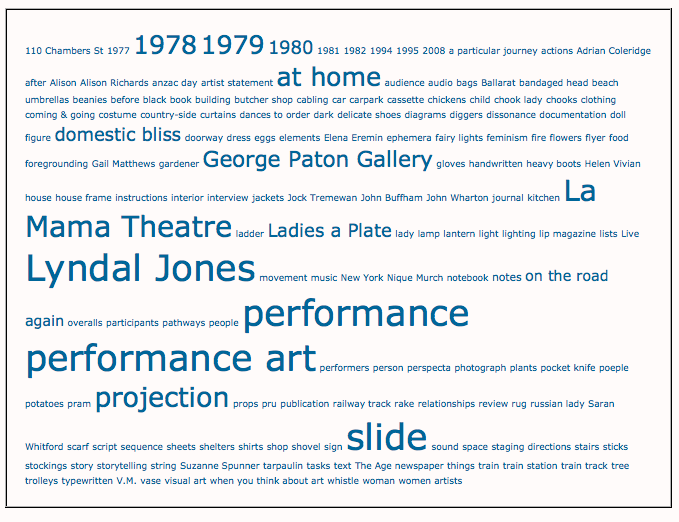

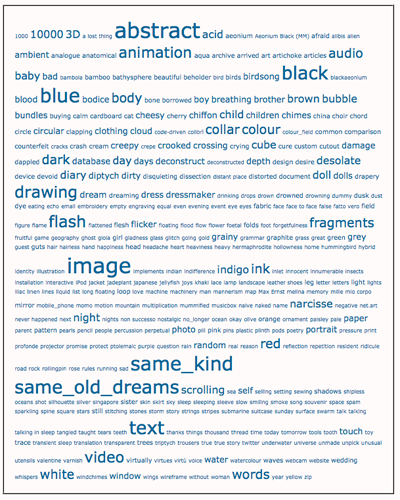

Figure 4.30 The At Home Series Archive - tag cloud (still under development)

(image with permission from Lyndal Jones)

(click to view larger image)

The archiving of this work has revealed many points of interest and many juxtapositions of content. Among other content/metacontent elements, the “tag cloud” (Figure 4.30) produced as part of this archive is particularly engaging as a means of entering the archival space. The keywords taken from the inventory description and the objects themselves most definitely have a recombinant poetics. Placing names and keywords together provide an interwoven fabric of relationships and points of entry to the content allowing access to this work in ways not possible before.

Figure 4.31 Screen capture of updated At Home series archive homepage with incorporation of recombinant groups

(image with permission from Lyndal Jones)

(click to view larger image)

Jones requested that the tag cloud be included on the homepage of the At Home archive to provide an additional point of entry to the content, alongside the layered, draggable items, and the recombinant groupings (Figure 4.31). This update to the interface has also been incorporated into the Blackaeonium and Atemporal archives as it is an additional means of engaging immediately with the content in the archive.

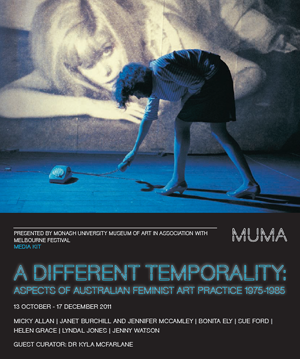

Figures 4.32 & 4.33 Images from the MUMA exhibition "A Different Temporality: Aspects of Australian Feminist Art Practice 1975 - 1985",

Promotional ephemera and installation of Lyndal Jones At Home series in the gallery (photograph by Lisa Cianci)

(click to view larger images)

The “At Home Series” archive and the Blackaeonium archival system that houses it were selected to form part of an exhibition of feminist art, curated by Kyla McFarlane, at the Monash University Museum of Art from October to December 2011 - titled “A Different Temporality: Aspects of Australian Feminist Art Practice 1975 - 1985”. The live online archival assemblage was displayed in the gallery space alongside physical artefacts and prints from the photographic slides taken of some of the performances by artist and photographer John Dunkley-Smith.

This digital archive was the only formal archival collection of work in that exhibition. As previously discussed, the significant works in that exhibition could only be shown for that brief period of time because the artists had kept this content themselves for a long time. In the catalogue, the artworks in the exhibition are mostly listed as “courtesy of the artist”[12]. The performance and variable media artworks are mostly still held in the artists’ personal archival collections, and from viewing the work in the gallery space, it was obvious that certain preservation strategies have already been necessary (to digitise video work for example) just to enable variable media works to be shown in that exhibition. It would be another significant project to document all of the works from this exhibition, and ensure their preservation for present and future audiences – perhaps something to consider as a future project.

The curators were asked for their impressions of the archival system and how it was used in the exhibition. Even before the exhibition was opened, the system was used to quickly retrieve the images needed for producing the exhibition catalogue. I was able to quickly find the high-res TIFF files based upon a snapshot provided by the curator. The curator’s low-res snaps were matched with the selected items from relevant series of images in the layered, draggable interface.

An email response from Francis E. Parker (one of the curators at MUMA) summarised the feedback from staff during the exhibition. Details of the email correspondence are in the PhD Blog along with my review of that feedback. While there was some insightful analysis made with regard to the way users approach the archive:

My sense was that the online archive worked better if one knew exactly what one was looking for than if one hoped it would yield up its contents.

(email correspondence with Francis E. Parker 10/07/2012)Some of the recommendations in that feedback were menu elements already implemented in the interface. At the opening of the exhibition, it was somewhat difficult to engage with the archive as the chair had been removed, so users were crouching and leaning over to try and access the interface (see Figure 4.33). Also, the keyboard had been removed, which meant that only clickable links were enabled: users were not able to type search criteria into the search interfaces.

It is a fair analysis to say that a casual user may initially need some guidance to interrogate the archive – it is more useful to have a purpose when approaching the archive. As Parker stated, the archive doesn't immediately reveal all of its contents. This is why the Tag Cloud, the Recombinant Groups Menu and the Draggable Layers are presented on the home page as a range of “points of departure”, but perhaps for some users, further instruction is required. The challenge now is to create a more explicit way of initially informing and guiding users without compromising the aesthetics of the homepage design. This is being addressed in the fourth prototype of the Blackaeonium archival system currently under development.

The At Home archive continues to be developed, to be tagged, to have recombinant groups created from its contents, and to be used to initiate reinterpretations of the original performance works.

Atemporal – a collaborative project in archival space

Artist Ilya Kabakov claims that our society needs artists not to create more information or imagery--we've got enough of that already--but to recombine and envision the culture we already have. Fortunately, today's artists have tools that enable them to reinterpret culture as never before.

from Empyre email list discussion, "Why art should be free" part 1 (Ippolito 2002).

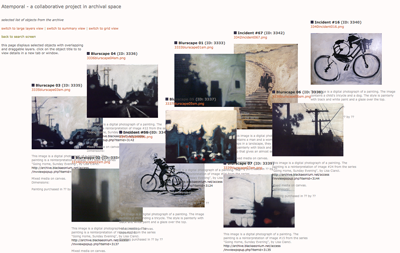

The Atemporal project is testing how the archival assemblage can be an artist’s tool for interpreting, reinterpreting and “future-proofing” artworks and creative content. This project involves a small group of artists sharing an archival space to create overlapping assemblages. The intent is to experiment with keeping and preserving content, and also making a space for play, experimentation and reinterpretation of ideas, concepts and content – to make new work and explore ways of presenting and re-presenting that work individually and in collaboration. This project uses methods and processes I have applied to my own creative practice through this research, and asks others to try working in the same manner.

Development of the Atemporal project is following a thread of this research whereby artists and creative practitioners use an “archival assemblage” as a method of developing new work. Artists have always used “remix” and juxtaposition implicitly in creating new work. This project (and the research behind it) reveals these common practices, and in doing so, engages in creating/curating/presenting recombinant and new works.

Through the processes occurring in this project, my intention has been to test the proposition that remix (using the archival assemblage) is a form of preservation – where storage, migration, emulation and representation of creative content naturally happens through the creation and re-creation of new work over time: the archive as a slow remix.

Figure 4.34 Image capture of the Atemporal archive homepage mashup

(image with permission of the artists)

(click to view larger image)

The name Atemporal comes from ideas discussed in Chapter 1: the Bruce Sterling Transmediale keynote speech “Atemporality for the Creative Artist” (Sterling 2010), and ideas relating to Frank Upward’s definition of the continuum.[13]

The project follows these initial ideas for methods and processes:

- The artist participants may choose a selection of items, records, artefacts. These may be a mixture of digital files, or digital documentation files of analogue items (video or still image of a physical object for example)[14]. The digital representation of each item must be uploaded to the online archive, so it must exist as a discrete digital file, with its own “spectacular aura”.

- The selection process is an important part of the creative practice. Items may be earlier works created by the artist, or may be in the custody of the artist (e.g. family or found photos/videos/documents/resonant objects). Some personal or close relationship to the item is important (unless random selection or serendipitous collection is a part of the creative practice for example). If possible, the artist should have permission to use the item if not created by him/herself (or the artist may claim “fair use” in the spirit of remix).

- Artists upload and document the selected items in an archival system and develop contextual and relational metadata for them. A Blackaeonium archival system iteration titled “Atemporal” (Cianci 2012a) has been set up for this project. Instruction and demonstration is given in how to use the archival system.

- Artists then develop new works (of any kind, in any kind of media) using or influenced by these archival items and metadata documentation. This could be digital/analogue/physical work of any kind - performance, installation, video, audio, still image, sculpture, painting, an Augmented Reality (AR) piece, a text, a publication, etc.

- Artists reflect on the process of creating these works and new works are also re-documented into the archival system.

- The archive becomes a site for online exhibition/publication with curation and re-curation of groups of items - artists can group/recombine/remix their own and/or each other's items into "exhibitions" or recombinant artworks or remixes. Artists may also choose to work collaboratively by remixing works of multiple creators, or by collaborating to curate certain Groups of items.

- A physical exhibition of these outcomes will be held (possibly a series of exhibitions, performances and events). There is also the possibility of creating a limited edition publication, of the kind produced in small numbers by artists and groups[15].

The project began in 2012 with six artists initially, but others are planning to join later in 2012 when schedules permit. Aside from myself, the artists already using the Atemporal archive are:

- Antony Catrice – mixed media artist, Magic Lantern operator and Archivist at Deakin University;

- Greg Giannis – new media and mobile media artist and Lecturer at Victoria University School of IT and Creative Industries;

- Carey Potter – mixed media artist and object maker;

- Dr Stefan Schutt - artist, musician, narrative researcher, “Ghost Sign” hunter and Senior Educator, Research and Learning, Work-based Education Research Centre, Victoria University;

- Anna Di Giovanangelo – virtual artist, collage artist;

These participants are all bringing unique skills and perspectives to the project:

- Having another artist/archivist collaborating in the project such as Catrice has been useful to gain the perspective of someone familiar with institutional archiving practices.

- Schutt is not an archivist, but has an understanding of the documentation process (especially in developing narrative) due to his own PhD project Small Histories (Schutt 2011), so we have engaged in many discussions on creating and using documentation systems, and how users might engage with the processes.

- Potter is very much an analogue artist with little experience of digital systems other than ubiquitous social media, so his perspective as a creator of physical objects and paintings is valuable to see how physical work translates when reinterpreted using digital tools (and he reinterprets digital media as physical artworks).

- Giannis creates works in a variety of media that range form large-scale projections on buildings to works that involve telecommunications systems to create collaborative works that rely on public participation. He also creates work that involves walking as performance, collaboration, subjective mapping and software writing, so this kind of work will add a component to the project that has not yet been dealt with in the archival system.

- Di Giovanangelo is a virtual participant, a collaged avatar with “zero history”[16]. It will be interesting to see how her work develops in the archival collaborative space.

A Selection of Works from the Atemporal Project

While new works continue to be made within and without the Blackaeonium archival system as my own personal archival assemblage, works are also forming in the Atemporal archival space. New series of works have been developed as a point of departure for initiating the Atemporal archive project.

Running Man (disambiguation), Elusive Truth, The Deep Sea, Antony Catrice 2012

Figures 4.35 – 4.37 Selected still images from the Running Man, Elusive Truth and The Deep Sea series, Antony Catrice, Atemporal Project 2012

(images with permission of Antony Catrice)

(click to view larger images)Antony Catrice works with analogue and reinterpreted works using complex processes involving Magic Lanterns and digitisation to image and video. As an artist and professional archivist, he has approached this experimental archive with a good knowledge of archival constructs and processes, but has never applied them to his creative work before. These series are experiments with process. The items come from his own artworks, and personal collections of curious objects assembled over a long period of time. These objects and artworks come together in the Atemporal archive in digitised form as a starting place for new series of work. Some of the fragments in his archival assemblage are already being used in collaboration with my own content to form new works.

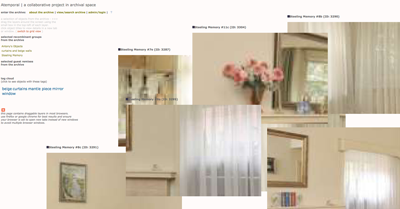

Steeling Memory, Glitches & Mirrors, Lisa Cianci 2012

Figures 4.38 – 4.41 Selected still images from the Steeling Memory series and Glitches & Mirrors series, Lisa Cianci, Atemporal project

(click to view larger images)The Rooms for the Memory series of still images form the basis for the Steeling Memories series (Figures 4.38 & 4.39), which are fragmentations of those original images. The images have been "appropriated" (in the spirit of “fair use”) from the real estate agent's photos of my grandparents’ house. After my grandmother died, it was a very large project for the whole family to deal with the house and everything in it - physically and emotionally. The photos used to sell the property are strange - they show everything with a fish-eye lens, but they don't show anything at all. Memory and what remains is disjointed. Many objects remain in the space. One must evoke one’s own memories to "haunt" the empty spaces and imagine what took place there.

Glitches and Mirrors (Figures 4.40 & 4.41) is a series of images that use the digital camera, reflections, screens and processes to glitch the digital devices in order to create images in the camera (without Photoshop filtering and editing) that have a particular aesthetic. Some works are images I have photographed, then displayed on computer screen and re-photographed with reflections from the room creeping into the pixelated, light-emitting images on the screen. Others are low-light interior photographs taken while trying to “fool” the camera in to capturing blurred images with movement. These works have been included in the Atemporal project to form the basis of new works using video and animation.

Ecotronics, Greg Giannis 2012

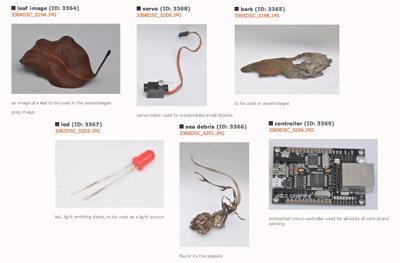

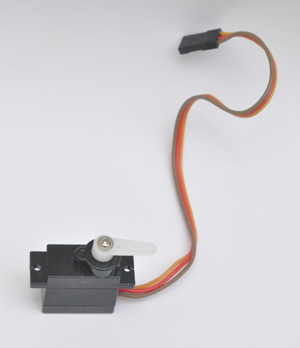

Figures 4.42 – 4.44 Selected still images from Ecotronics series by Greg Giannis, Atemporal project 2012

(images with permission from Greg Giannis)

(click to view larger images)Giannis has assembled a selection of objects (items from nature and electronic parts) as a starting point for new works. These items are symbolic of many aspects of Giannis' creative practice, so it is intriguing to see what directions the work will take.

Blurscapes & Incidents, Carey Potter 2011 – 2012

Figures 4.45 – 4.47 Selected images from Blurscapes and Incidents series by Carey Potter, Atemporal Project

(images with permission from Carey Potter)

(click to view larger image)Blurscapes (see Figure 4.45) is the first collaboration to come from the Atemporal project. Potter has created the paintings based upon my series of images (from the Blackaeonium archive) titled “Going Home, Sunday Evening”.

The “Incidents” (Figures 4.46 & 4.47) are an ongoing series of paintings that Potter creates as stand-alone objects, or as recombinant groupings that form and reform a multiplicity of potential narratives. These paintings, now digitised for the Atemporal project, are ideal content to remix with other series in the archival space.

Altes Deutschland, Stefan Schutt 2012

Figures 4.48 & 4.49 Selected images from Altes Deutschland series by Stefan Schutt, Atemporal project 2012

(images with permission from Stefan Schutt)

(click to view larger images)Stefan Schutt’s video fragments form a part of his assemblage of narrative works. These fragments are personal in nature - the video captured during his travels in Europe and Israel while tracing a family history that itself was fragmented and mysterious until he undertook his personal research journey. His intent is to see what will emerge from working collaboratively with others interested in memory and "hauntologies".

There are certain commonalities in our work such as, hauntologies, “machines of yearning”, our use of process and layers of technology (both old and new media in analogue and digital formats). Recombinant Groups are beginning to form in the archive such as: “Curtains and Beige Walls”, “Incidental Story 1” and “Running Man (disambiguation)” (see Figures 4.50 – 4.52)

Figures 4.50 – 4.52 Recombinant Works from the Atemporal project, 2012

(images with permission from the artists)

(click to view larger images)

Feedback from artist participants is being collected informally as it occurs through discussion and email correspondence, and these communications are being documented in the PhD blog. The feedback is currently impacting on the Blackaeonium archival system. Recommendations for improvements to workflow, and suggestions for new interfaces will assist in improving the system to further enable the incorporation of the archival act into the creative act (and visa-versa). One particular area of discussion has been the process of entering and uploading content into the archive (see Figures 4.53 & 4.54). At present the system still requires mostly manual entry of required content. While the technology is there to partially automate some of these processes, we are debating the benefits of actually automating the process as much as possible.

Figures 4.53 & 4.54 Selected blog entries relating to the Atemporal project and Blackaeonium archival system fourth prototype development

(click to view larger images)Systems such as Facebook and Wordpress contain functionality such as multiple file upload[17], which does speed up the process somewhat, but my concerns with these processes are how they devalue the content that is being uploaded. Looking at online content in social media systems (examples are extremely easy to find), one can see how easy it is to upload a large quantity of images for example, and then fail to document them properly – there is a lack of description about the creator, content, or of artistic intent. Somehow a balance must be struck – to improve the interfaces to include some common automation processes, without dissipating the value of the individual item.

Audience Participation & Engagement - Guest Remixes

Archives are always remaking themselves. They are constituted not only by the materials contained within them, but by those who (re)turn to them. Nothing happens until then.

(Renton & Scott 2002)

Agency in digital, interactive, networked environments

There are many roles for the user and many, subtle levels of agency in networked interactive works and in online systems such as those investigated during the research project, as has been shown in this chapter involving those that "(re)turn" to the archives created with the Blackaeonium archival system. The Rhizome.org Artbase and the PAM video archive are two other examples of systems with many levels of agency. The extremes of these roles could be called the “creator-user” and the “audience-user” – and they could potentially be the same person. These users navigate the virtual space of the online digital archival assemblage. Through navigation, the content within the assemblage forms and reforms narratives, and may evokes thoughts, feelings and memories through interaction with the work.

The observer turns into traveller who structures the text/space in a new way […] depending on his or her experiences, associations and momentary decisions.

(Dinkla 2002, p.36)The Blackaeonium archival system, as a system situated on the Internet, can be changed or influenced by user navigation, interactions and trajectories. The Group construct was developed as a creative construct rather than an archival construct because its function is to allow saved groupings of objects that could have any level of context – from a random group to a purposefully selected one based upon careful searching and browsing. An object can belong to many different groups, and these groups can be created by both the creator-user and the audience-user. Thus, over time, it is possible to map both how creator-users intend to present content, and construct narratives, and also how audience-users choose to experience the content, interact with it, and reorganise it to suit their own whim or purpose, to create other content or other stories. The Group has become the means of saving objects as recombinant works as shown in Figures 4.50 – 4.52.

Figure 4.55 Tag Cloud from the Blackaeonium archival system

(click to view larger image)

Tagging[18] is also used in the Blackaeonium archival system to create links and trajectories from keywords. Anyone can tag any object if they have been given “guest” access to the system. As tags build up over time, the “Tag Cloud” as shown in Figure 4.55 changes and forms a new narrative, a new description of the collection, and a new map of the virtual terrain with peaks and valleys, points of interest and multiple points of entry to the content. The tagging of content in the Blackaeonium archival system was originally open to public users, but the current prototypes have closed this functionality so that only creators and selected guests may tag the content in the archive.

There is a tension in wanting to have one’s work as open as possible, to have audience participation in the archive, but at the same time, there needs to be some control over what is being manipulated. The system has already experienced malicious attack, in the first and second prototypes. Although there are ways to avoid this such as using “Captcha”[19] form validation widgets, for the moment, the tagging and guest remixes are closed to general public usage. It is possible for any user encountering the archive online, to request a guest membership to the system to participate in the remixes, the tagging of objects, and engage with all of the archival content. In this way, it becomes more of a deliberate act of participation and engagement, not just a random encounter with a website that allows free data manipulation.

Creating guest remixes

Forty “Guests” were personally invited by me, via email message, to enter the Blackaeonium Archive, and asked to navigate the archival space to find and select items that could then be saved as a “remix group” with some text by the remix author. The purposes of this endeavour were:

- To have audience-users engage with the archival assemblage in a creative way, and test the Blackaeonium archival system in a more meaningful way than the standard user-testing scenarios recommended for websites;

- To encourage participation by the audience; and

- To save these remixed works as another point of entry to the archival assemblage – created by the audience.

A set of instructions was developed as a PDF document to assist the “Guest Remixers” to enter the system and use the various interfaces to create remixed works (see Appendix 5 - User Testing and Guest Remixes Questionnaires & Surveys). The invited guests come from a wide range of age groups and levels of technological experience with web systems and interactive artworks. Some users had familiarity with my work prior to creating a guest remix, others had never seen the work before, nor engaged with online interactive artworks.

Figures 4.56 – 4.58 Screen captures of selected Guest Remixes

(click to view larger images)

The response to my invitation was deemed successful because of the number of remixes created, and because the remixes are mostly well considered, and definitely in the spirit of the archival assemblage. Some interesting combinations were made that I may eventually incorporate into new works such as Unforced Confession, Unhalved, Double Happiness and Fantastic Voyage.

A "Survey Monkey" (Survey Monkey 2012) questionnaire was created to compile formal feedback from the Guest Remixers to see if they found the process difficult, if they enjoyed it, had any recommendations for making the process easier, or to recommend developments for my “wish-list” of functional elements to develop for the Blackaeonium archival system (see Appendix 5 - User Testing and Guest Remixes Questionnaires & Surveys).

The feedback recommendations mostly related to having more information at the start to show what the outcomes would be like – or at least point more directly to existing remixes to show what the guest would be creating. This feedback is being taken into consideration in the development of instructional information for the Blackaeonium archival system. Again, the challenge will be to present this instructional information seamlessly in the system without compromising the aesthetics of the interfaces. Currently, instructional material is being developed as adjunct content to be accessed when required, not initially presented to the user on visiting the website.

The Guest Remixes are being “tiered” in different social media systems such as Facebook and Twitter, and the Indigo Aeonium portal is also being used to promote and proliferate the content to the audience. Using the Indigo Aeonium Wordpress portal site has raised an issue about where “comment” information from the audience should be stored. I am still uncertain about how much to develop the Blackaeonium system to allow comments in the archive. It was an area flagged for future development - perhaps for guests only, like the tagging and the guest remixes. In a way, the remixes already allow for comment in the description field. It has not yet been decided whether comments should be allowed in the Inventory by guests with individual logins so it would be possible to track who added the comments and tags.

What can be concluded is that the user testing undertaken from an artist’s perspective and from an engaged audience perspective has been more useful than the earlier system testing. More insightful information is coming from these participant projects and this is affecting the system development.

In the same way that the Same Old Dreams “Memorypool” database has developed over time, affecting the meaning and interpretation of the entire project, the various archival assemblages developed through this research project are growing, changing and developing new creative content through use, collaboration and participation. To revisit the earlier quote by Ketelaar,

Every interaction, intervention, interrogation, and interpretation by creator, user and archivist is an activation of the record (Ketelaar 2001), each in a new ‘concept space' (Ketelaar 2012)

We are working in a conceptual archival space, interacting, intervening, interrogating, interpreting, re-interpreting and thus activating the contents of the archival assemblages as methods of creative practice. The archive enables the creation of something new through reinterpretation of the content it keeps and documents, and those that access it through collaboration and engagement.

top of page | homepage & table of contents | next section - conclusion

Endnotes

[1] Founded by ACW, the Melbourne Choir of Complaints is one of the worldwide choirs of complaint started in Helsinki by Tellervo Kalleinen and Oliver Kochta-Kalleinen (Kalleinen & Kochta-Kalleinen 2005).

[2] ACW has an interest in the archive as site of power, what is kept and lost, and what is remembered and what is forgotten. For example, projects such as “SPEECH and What Archive?” (A Constructed World 2009) include examination of the theory of archives as part of contemporary art discourse .

“SPEECH and What Archive? will address the idea of what it is currently possible to say and what gets kept and thrown away; what is saved and what is rejected or forgotten. […] What-we-can-save and on-behalf-of-who becomes an issue in terms of groups and democracy that can be applied to our habitat in general, a library, a publication or a shoebox of memorabilia that an individual has safely put away. We will also consider examples of the here-and-now to see what can be saved from a disorganised, cluttered and confused present. Through using the Internet, video, speech, writing and openness to any media we look to move between the space of the expert and the institution and private longings and desires that can help us form a better picture and account of what we collectively want.” (A Constructed World 2009)The blog for SPEECH and What Archive contains comments from participants, and links to seminars, meetings, projects and other “evental” platforms. This project is ongoing and continues in many locations on an international scale and involves many collaborators and participants from many global locations.

[3] Joseph Beuys , “How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare” (Beuys 1965), An image of this performance may be viewed at this URL: <http://clancco.com/wp/2010/11/fair-use_performance-art_fixation_fair-use/>

[4] In one case, an image was used in the “Eels #4 Reader” of Salvador Dali and Gala holding a copy of the painting "The Lacemaker" by Vermeer whilst standing in a pool of water at Cap Creus in Catalan, titled "La Dentellière baptisée par Dali et Gala à Cap Creus, en 1957" – this required a fair amount of research to determine the source of the image and the painting Dali and Gala are holding.

<http://acw.blackaeonium.net/access/invviewpopup.php?itemid=63>Another example involved the misspelling of Glenn Gould as “Glen Gould” in the Reader, and the fact that the image depicted was of Glenn Gould in costume as a fictional character. Through online research it was discovered that the image is a captured frame of a black and white video of Glenn Gould as “Karlheinz Klopweisser” (1980). The image used in the Reader shows Klopweisser (Gould) performing on Glenn Gould’s television show. Klopweisser is shown making music using a metal detector and several suspended picture frames in the television studio. The YouTube video link (YouTube 2008) discovered through the use of a search engine shows this video as a promotional piece for a CBC broadcast - it is a humorous video clip, and use of the image by ACW is intended to make a humorous reference to this kind of experimental performance in relation to their own performance with live eels.

[5] See the archival record in the ACW Blackaeonium archival system showing contents page of the Reader at <http://acw.blackaeonium.net/access/invviewpopup.php?itemid=4>

[6] “Contributor: An entity responsible for making contributions to the content of the resource. Examples of a Contributor include a person, an organization or a service. Typically, the name of a Contributor should be used to indicate the entity.” (Dublin Core 2005)

[7] “Coverage: The extent or scope of the content of the resource. Coverage will typically include spatial location (a place name or geographic co-ordinates), temporal period (a period label, date, or date range) or jurisdiction (such as a named administrative entity). Recommended best practice is to select a value from a controlled vocabulary (for example, the Thesaurus of Geographic Names (Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Names: <http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabulary/tgn/>). Where appropriate, named places or time periods should be used in preference to numeric identifiers such as sets of co-ordinates or date ranges.” (Dublin Core, 2005)

[8] Not all Dublin Core elements had been used thus far in the Blackaeonium archival system. The three details fields in the Inventory data table allow for a wide range of information to be documented for elements that do not have distinct fields such as participants and language. Through working with artist participants, however, it was apparent that some additional fields would be useful, relevant, and make data entry easier because one would be able to preset and select options from a list rather than typing free text.

[9] Somewhat coincidentally, my very first archival project as a student at The University of Melbourne in 1993, documenting the slides from the Ewing and George Paton Gallery (GPG) (see Introduction) included Lyndal Jones’ work. Some slides from her performances were documented as part of that project – the “At Home Series” was performed at the GPG and at La Mama Theatre in Carlton. Inclusion of the archival documentation of Jones’ work in an iteration of the Blackaeonium archival system is part of a creative archival continuum. The research, which tentatively began years before this PhD research project was undertaken, has come full-circle as this phase of the research reaches its final stages.

[10] Jones’ current major work, “The Avoca Project: Art, Place and Climate Change” (Jones 2011) is a long-term (ten year) international project located in regional Victoria. The project involves the Watford House (Swiss House) site in Avoca as a location for a number of installations and performances involving diverse fields of enquiry and many local and international participants.

[11] Archives assistant for this project, Dr. Julia Cianci, is also my sister. She has a PhD in Medicinal Chemistry from The University of Melbourne and while working on the At Home archives, was undertaking a Graduate Diploma in Information and Knowledge Management at Monash University while also employed in research work at Melbourne biotech company Biota (<http://www.biota.com.au/>). I was extremely fortunate that her 100-hour work placement (a requirement of the Grad. Dip. At Monash University) coincided with the archival project for The At Home Series, and she was able to undertake a large portion of the archival documentation at Inventory level.

[12] except for the photographic works of Mickey Allen which were purchased by the National Gallery of Victoria

[13] Theories and concepts that form a background to this project development are:

- Recombinant art using analogue and digital media;

- Remix (Navas 2011a),

- “Hauntology” – Derrida (Fisher 2006);

- Assemblage and rhizomatic structures for traces, flows and narratives (Deleuze & Guattari 1987), (Rhizome.org 2006);

- An archival continuum of creative practice (Upward 2005);

- Atemporality (Sterling 2010) and space-time distancing (Upward’s term for archiving);

- Slowness and intensity of memory (Kundera 1996, p39);

- Soft collision and montage - Eisenstein (Smith 2004).

[14] A minimum of 3 items may be selected (the maximum could be over a hundred, keeping in mind that each item must be uploaded and described).

[15] Another outcome is to develop workshops for artists to learn how to adopt archival practices into their own creative practices: “future-proofing” for creative practitioners. Outcomes of these workshops may also be exhibited and published. (See Chapter 2 for details of educational modules being tested with students at Victoria University School of IT and Creative Industries)

[16] A reference to William Gibson’s novel of the same title (Gibson 2010), “Zero history” refers to a person without a traceable documented history.

[17] Multiple file upload usually involves uploading the content first, then going to another interface to add contextual information about each individual item in the group. The problem here is that users often don’t bother to spend much time on the second step, and so these systems become filled with a large quantity of content, without quality documentation.

[18] A tag is a (relevant) keyword or term associated with or assigned to a piece of information (like picture, article, or video clip), thus describing the item and enabling keyword-based classification of information it is applied to. Tags are usually chosen informally and personally by the author/creator or the consumer of the item — i.e. not usually as part of some formally defined classification scheme. “Tagging systems are excellent at the task that they were designed for---allowing a large, disparate group of users to collaboratively label massive, dynamic information systems like the web, media collections of millions of images, and so on.” (Heyman 2008)

[19] “A CAPTCHA is a program that protects websites against bots by generating and grading tests that humans can pass but current computer programs cannot.” (Captcha 2010)

top of page | homepage & table of contents | next section - conclusion

this page produced by lisa cianci on her website www.blackaeonium.net

comments and queries to lisa's email address on scr.im (for humans only)

created 01/12/2011

last modified 30/07/2012