homepage & table of contents >> chapter 1

On Recombinant Poetics, Virtual Spaces, Remix and the Archival Continuum: an overview of the fields of practice and conceptual foundation for the project

Art is either plagiarism or revolution.

Destruction is also creation.

Art is not about itself but the attention we bring to it.

Marcel Duchamp (Sanouillet & Peterson 1973)

Because this research project is creating artwork through archival processes and the recombinant poetics of remixed and reinterpreted creative content, it must necessarily be framed in terms of a history of creative practice – from significant artists in the first half of the twentieth century such as Marcel Duchamp, through to recent artworks created in virtual, online spaces by artists such as Selavy Oh (whose name is a play on Duchamp’s female alter-ego Rrose Sélavy) and demonstrates the ongoing respect for Duchamp’s profound contribution.

The review of the community of practice for this research project is a brief examination of selected artists and scholars covering the fields of contemporary art, digital media, web technologies, variable media preservation and archival science.

Recombinant Poetics: artists who have worked with their own archival assemblages to create works (from 100 years of art practice)

Figure 1.01 Marcel Duchamp, Boîte (The big box) (Duchamp 1966)

(image with permission from the museum - Universalmuseum Joanneum)

(click to view larger image)

The Boîtes en Valises by Marcel Duchamp (1966), are a series of re-interpreted artworks as a set of miniatures – a “museum in a suitcase” (Figure 1.01). Duchamp made a number of these artworks which include small reproduced versions of his famous artworks such as Nude Descending a Staircase, The Large Glass (his most important artwork, now in the Philadelphia Museum) and Fountain (the infamous porcelain urinal). These miniature works are assembled in fold-out boxes or suitcases with individually labeled contents. These "artworks as assemblage" embody the recombinant poetics at the heart of this research project because they are a portable remix of previous artworks, and at the same time - a preservation strategy: stored; emulated; migrated; re-interpreted; consisting of multiple copies in multiple locations.

Conceptually, Duchamp’s work can be compared to many areas of new media art practice such as the use of appropriation in his “Readymades” involving the remix of found items in sculptural form, and the remix of his own content in the Boîtes en Valises. As Okwei Enwezor, the internationally important South African curator (International Center of Photography in New York) and art director (including the Documenta 11 exhibition in Germany 1998 – 2002) recognises:

La boîte–en-valise is not only a sly critique of the museum as institution and the artwork as artifact, it is fundamentally also about form and concept, as ‘it reveals the rules of a practice that enable statements both to survive and to undergo regular modification' [Foucault]. (Enwezor 2008, p. 14)

These Valises operate as analogue multiplicities and assemblages, the content now distributed across many global locations, exhibited in many physical spaces over many years. Duchamp may have claimed that these works were financially motivated “small business” and a dismissal of museum archiving practice (Schaffner 1995), but it has been suggested that underlying motives may have included anxiety about the vulnerability of artworks such as The Large Glass, which sustained damage during transportation. The Valises are an autobiographical assemblage, a “life-long summation”, and an archival collection – possibly a post-custodial method of preservation for creative content in a distributed form[1].

Joseph Cornell, an artist widely known for creating assemblages in wooden boxes using collage techniques and found objects, demonstrates through his work, the analogue remix as a means for creating new, recombinant narratives. Works such as Homage to the Romantic Ballet 1941 and Untitled (Penny Arcade Portrait of Lauren Bacall) 1945-46(Hartigan 2003) involve the juxtaposition of images and objects framed within glass-covered wooden boxes. These delicate objects contain many potential stories – imagined histories of the items within (where did they come from, and why are they all here together?), and lead us to invent new meanings for the elements brought together by Cornell’s artistic intent.

It is his lesser-known films such as Rose Hobart (Cornell 1936) that have more recently resurfaced and found resonance in the new media arts community for their recombinant poetics (Figure 1.02).

Figure 1.02 Joseph Cornell, “Rose Hobart”, still image from the film. 1936

(Cornell 1936) image capture from UBUweb website

(click to view larger image)

Rose Hobart is a remix (what we would now call a “post-production” remix), of footage taken from the 1931 film East of Borneo – a “jungle B-film” (UBUweb 2001) starring the actress Rose Hobart.

Cornell sampled the film, removing over two-thirds of the content (almost every shot without Hobart), until all he was left with was a strange and eerie film, tinted blue to signify the world of dreams. Many of Cornell’s works in film and the mixed media assemblages, involved “mythologised” movie actresses of the day. These films were not shown to large audiences at the time, Cornell was rather reclusive and not prone to exhibiting his work. It was through Duchamp that the Surrealists came to know him.

When Rose Hobart was shown at a screening in New York in 1936, many of the Surrealists came to view it as they were in town for the first Surrealist exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art. Salvador Dalí knocked over the projector and stormed out during the screening (reportedly) claiming that Cornell had stolen the idea from his subconscious.

This film is an early example of remix and reinterpretation using mechanical technology rather than digital technology. It is also an example of how the artwork is a part of a continuum of creative practice. If not for Cornell’s remix, Rose Hobart the actress, and the “B-grade jungle film” might have slipped into obscurity. Many new media artists have found meaning in Cornell’s work: he and Duchamp form a starting point in the lineage of modern artists working with found materials, remixed media, and assemblage.

No one made films even remotely similar to Cornell's for almost thirty years, and even now the perfect opacity of his montage remains unrivalled.

(UBUweb 2001)In the second half of the twentieth century, Fluxus emerged as a network of artists, musicians, designers and writers. Organised and named by Artist George Maciunas in the early 1960s, and influenced by Duchamp and the Dada movement, Fluxus became well known for many of the artists and musicians that formed part of the network, such as Joseph Beuys, John Cage, George Brecht, Nam June Paik and Yoko Ono. Fluxus is based upon a philosophy of anti-commercialism in art, of simple ideas, short texts, events and performances, and the recombination of found objects, everyday items, and a “do-it-yourself” attitude.

There were as many different ideologies and interpretations of Fluxus as there were people, and the chance to work with people of different opinions was one of the most challenging aspects. Anything could be included, from the tearing up of a piece of paper to the formulation of ideas for the transformation of society. (Beuys 1982)

Fluxus artworks include the documentation of conceptual ideas for performances as “event scores”, similar to musical scores that described a potential or actual performance (History of our World 2009). Another art form in which Fluxus artists like Maciunas engaged, was the creation of Fluxus Boxes or “Fluxkits” - assemblages of various kinds of media including ideas for artworks, that were assembled in plastic or wooden boxes (MoMA 2010).

Fluxus is significant in the context of this research because it forms part of the continuum of practice following on from Duchamp, and because of the use of “intermedia”[2], variable and ephemeral media formats (found objects, analogue audio and video, mechanical technologies) including performed “events” or “happenings”. Fluxus art also involved the remix and reinterpretation of media in many different forms from reinterpreted performances, to represented physical works and published texts (Friedman et al. 2002).

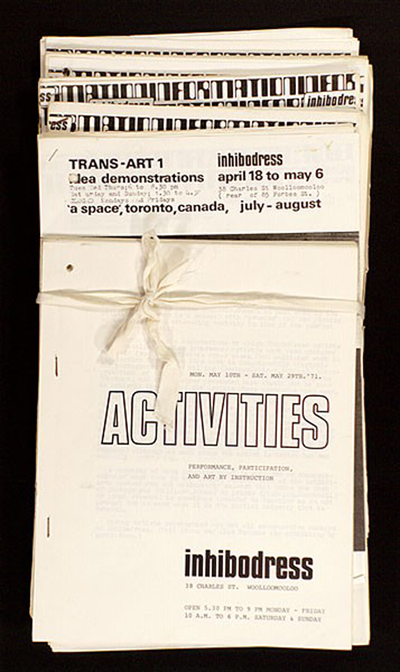

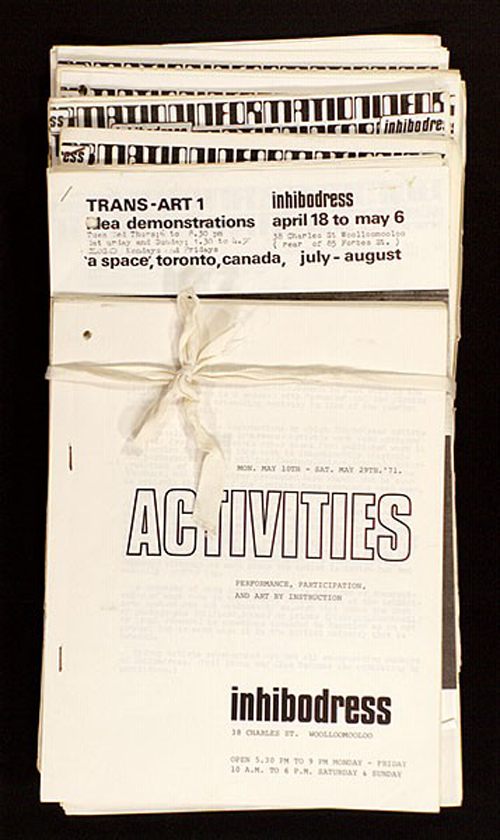

In Australia, in the early 1970s, artists Mike Parr, Tim Johnson and Peter Kennedy established "Inhibodress", a gallery space and artists' cooperative that produced conceptual art, performance art and video. Inhibodress was similar to Fluxus in some ways. Event and performance were a means of engaging and sometimes shocking the audience.[3]

Figure 1.03 Mike Parr “A collection of works from Inhibodress Archives” (1970-72)

Accession No: NGA 73.561.1-11, Held by the National Gallery of Australia (NGA 2012)

(image with permission from the NGA and Mike Parr)

(click to view larger image)

Like Fluxus, the performances that were a part of Inhibodress were documented through “performance instructions”. Parr is a meticulous documenter of his performances, and the early Inhibodress instructions, although not all performed at the time in the 1970s, inform his later creative practice (Figure 1.03). His work clearly demonstrates how artists use past work to inform future work. The MCA in Sydney now holds the Inhibodress archive, donated by the artists.

One example of this continuum of creative practice through reinterpretation of past work, is the performance instruction from 1972 titled Nail Your Hand to a Tree, one of hundreds of short pieces – some performed, some not performed.

We discussed the details on the phone. Mike wanted to enact a paradoxical performance instruction that he conceived in 1972 as Nail Your Hand to a Tree […] like many other early pieces, it now appears not so much as a definitive statement of the human – possibilities of being and acting, the relation of the human and natural – but an amplifier, the means to an epiphany, to a resonant crystalline moment in which revelation can be given a presence that must be addressed. (Bromfield 2002)

Nail Your Hand to a Tree was impossible for Parr to perform as a solo artist because he only has one hand. This is part of the “paradoxical” meaning of the work, but in 2002, Parr re-interprets this work as Malevich (a political arm). His motivation for the performance is “an attempt to enact the epiphanic potential of the piece for the first time, to engage its revelatory possibilities in the present moment, in relation to the current state of his printmaking, sculpture and environmental works, their political and social possibilities.” (Bromfield 2002)

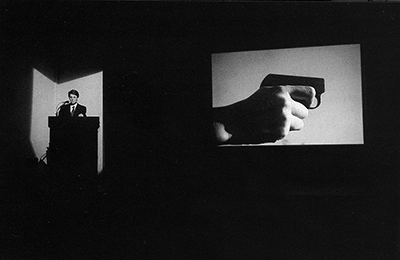

Figure 1.04 Performance by Mike Parr, 2002, “Malevich (a political arm),(Bromfield 2002)

(image with permission from Mike Parr)

(click to view larger image)

Parr coordinated a team of artists and friends to assist him to perform this work where he spends 24 hours blindfolded, with his right arm nailed to a gallery wall (Figure 1.04). The performance is fully documented with video and photography, and another artist is required to hammer the custom-made surgical steel nails through Parr’s arm, and remove them at the end of the performance.

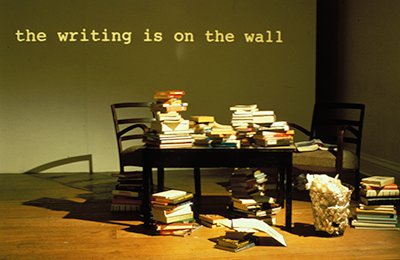

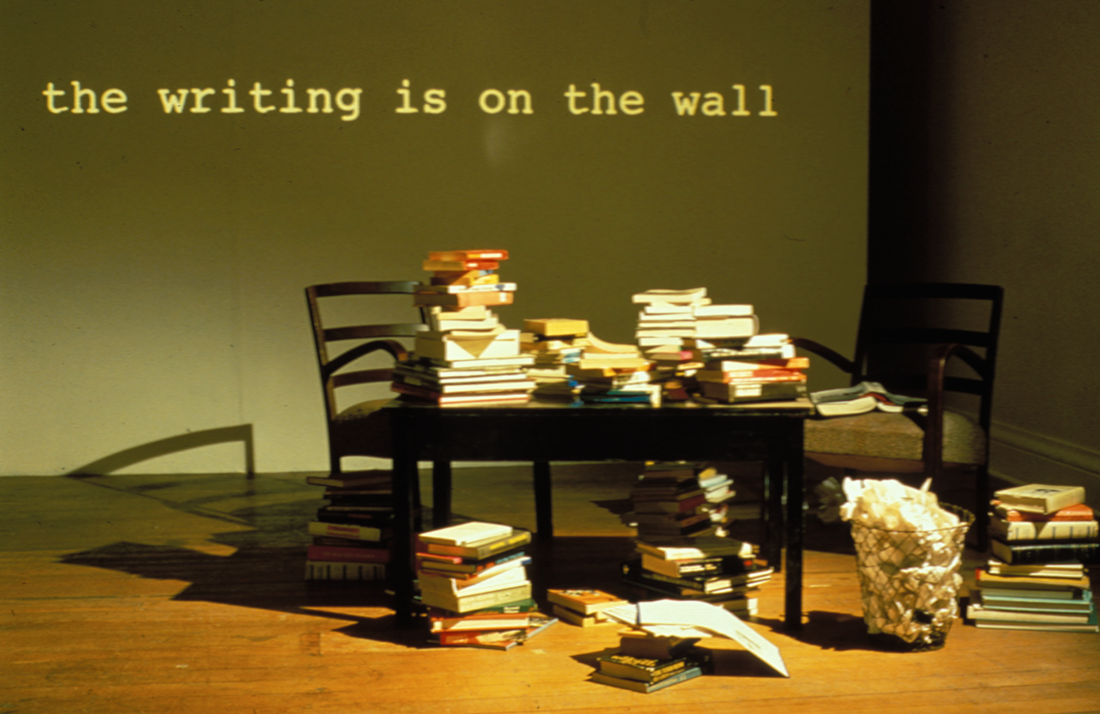

Following along the continuum of creative practice and recombinant poetics, Australian artists Lyndal Jones and A Constructed World (Lowe & Riva) also use ephemeral, variable media, and open strategies in their installations and performances. Both Jones and ACW have worked with the archive in their creative practices, and both use reinterpretation and remixing of content to create new work, or new presentations of their work.

Jones’ “The Prediction Pieces” was a series of performances from 1981 to 1991 where “Jones explored the way humans arrange the idea of the future within their minds” (Engberg et al. 2008) (Figures 1.05 & 1.06). The documentation or trace of these events has become a reinterpreted archive of variable media held by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney (Cramer & Jones 1992). Recently, these works have been further reinterpreted due to digitisation and preservation strategies that are required to keep the content accessible over time.

Figure 1.05 - Figure 1.06 Lyndal Jones, images from the Prediction Pieces

(images with permission from Lyndal Jones)

(click to view larger images)

ACW uses the web, and print publications to create remixed and reinterpreted versions of performed and installed works. The performances and installations are also reinterpreted each time they are reconstructed in a different location. The work Explaining Contemporary Art to Live Eels #4 (Figure 1.07) is located in a creative continuum influenced by Joseph Beuys, Allan Kaprow, and Sigmund Freud.

Figure 1.07 A Constructed World, selection of items from the ACW archive showing

“Explaining Contemporary Art to Live Eels #4”, (ACW 2008a)

(images with permission from ACW)

(click to view larger image)

This work is a reinterpretation of the original “Explaining Contemporary Art to Live Eels” performance presented on three continents by A Constructed World in 2004-2005 where different “fungible” elements were used in the installation, and different participants took part in the performances. The works are documented via image, text and video[4].

Virtual Spaces: artists who create artworks using the Internet

The Internet is itself neither exclusively an object, nor collection of objects, nor a process, nor bundle of processes or protocols. As in the quantum field, what it is depends on who's looking, and at what. A medium which lends itself to the creation of a fictional space for the enfolding and unfolding of intertwined ontologies about space-time knowledge systems, histories of ideas and human consciousness. Looping story strings, which resonate through different worldviews and contemporary global concerns.

(Francesca Da Rimini - from Arts in Australia 2006)

New media artists who work with a recombinant poetics, using remix or other methods of creating works that follow the continuum flow in ways that resonate with this research project are: Francesca Da Rimini (Australia); Martine Neddam (Belgium); Occulart - Geoff Lillemon (Netherlands); Alan Sondheim (US); and Selavy Oh (Second Life).

Francesca Da Rimini is a founding member of the cyber-feminist artists' collective VSN Matrix (Da Rimini et al 1991) and is known in the Internet art community for her remixed, “recombinantly poetic” interactive website DollSpace (Da Rimini 1997).

Figure 1.08 – 1.10 Francesca Da Rimini, Dollspace (Da Rimini 1997)

images captured from the Dollspace website (with permission from Francesca da Rimini)

(click to view larger images)

Da Rimini remixes content from across the Internet to form her “deep dollspace zero” (Figures 1.08 - 1.10). She creates a hyperlinked non-linear narrative involving sex, violence, love and death. The sampled elements in Dollspace form a fictional story with flows, dead-ends, loops and recursions. Da Rimini’s work relates to my own in it’s use of ubiquitous web technologies to develop interactive artworks, and explore multilinear narratives. Dollspace was influential in the development of my project Same Old Dreams.

Geoff Lillemon (known as Occulart) creates artworks unlike any other user of the Adobe Flash software application. His website (Lillemon 2006) hosts a growing collection of animations. The original animations were created with Flash (Figures 1.11 - 1.13), the more recent ones use HTML5 and associated scripting languages in a mix of web media including text, image and video.

The Flash pieces in the Occulart Archive are works that combine visual stills and loops of different styles to form pulsing and undulating animations. Lillemon has created interactive collages whose influence can be traced back to Max Ernst’s surrealist collages, such as A Little Girl Dreams of Taking the Veil (Ernst 1930).

Figure 1.11 – 1.13 Examples of animation by Occulart (Lillemon 2006)

(images with permission from Geoff Lillemon)

(click to view larger images)

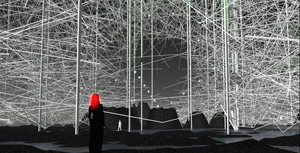

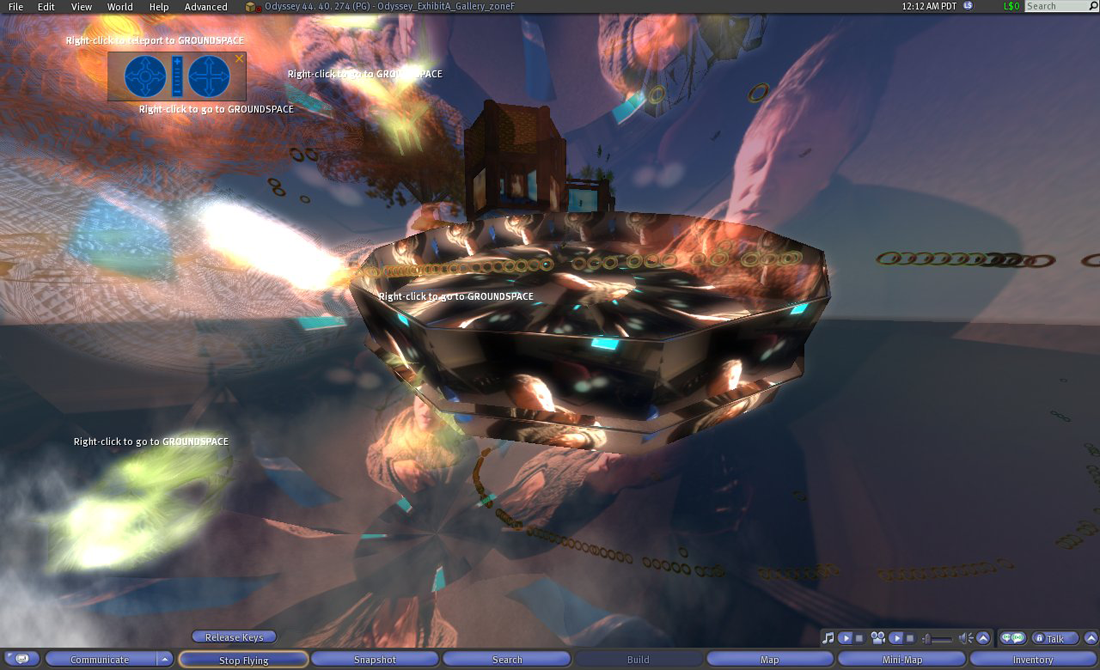

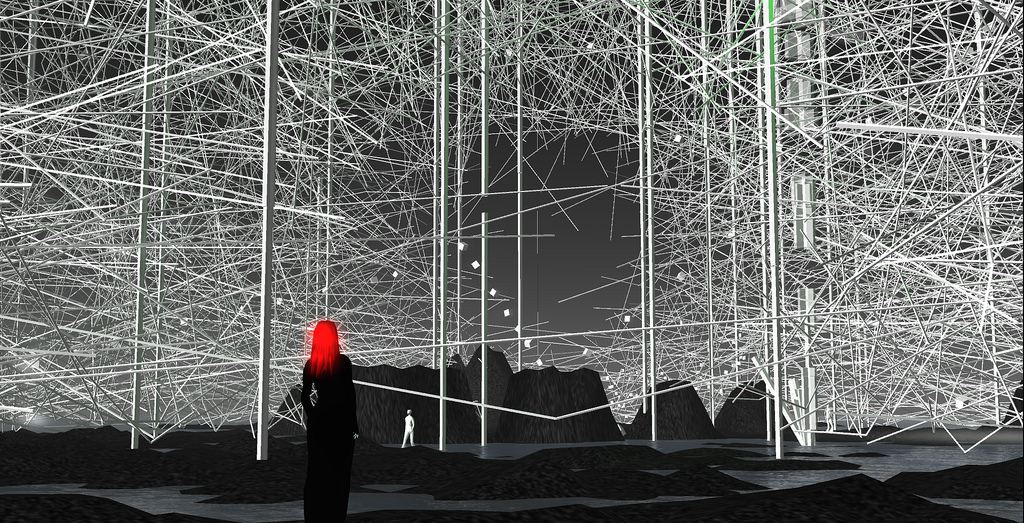

I was interested in how artists who work in 3D virtual spaces like Second Life (2007), and use a process described as “tiering” (Dena 2007) to document their work through various online social media systems and applications[5], may potentially be employing this strategy as a form of archiving or at the very least, a method for minimising risk with regard to the loss of creative content. My research was particularly influenced by two artists who create works in Second Life: Alan Sondheim (Sondheim 2011); and Selavy Oh (Oh 2009).

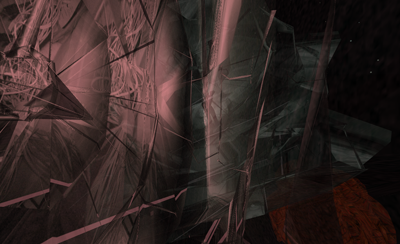

Alan Sondheim is an artist, musician and writer from New York who has exhibited, performed and lectured widely in the US and Europe for over forty years. He continues to create works across a range of media, including performed works in Second Life. His work is often ephemeral, and he documents his work by capturing video, audio, and still images of virtual and physical performances, then locates them on his website and other online spaces such as email lists, blogs and other social media platforms[6]. These images…

Figure 1.14 –Alan Sondheim – Takeover 1 (Sondheim c.2010b)

Figure 1.15 – Moth (Sondheim c.2010a)

still images of artwork created in second life (images with permission from Alan Sondheim)

(click to view larger images)

…show two of Sondheim’s Second Life installations (Figure 1.14 & 1.15). The remixed elements visible in the images include 3D models mapped with mixed content including photographic self-portrait images of Sondheim himself.

The elements I make aren't ephemeral in a way, but kinds of notations, part of a flow; archiving preserves the flow, not as stasis (since the work moves on), but as artifacture...

(personal email correspondence with Alan Sondheim 17/05/2010)[7]These Second Life works often include avatar figures dancing with contorted limbs that wouldn't be possible in the physical world, and 3D models that merge and pass through each other – aspects of 3D animation that would normally be avoided in games or videos that attempt to emulate the physical world. Sondheim uses these “glitches” and mistakes in the 3D world to emphasise the weaknesses and foibles of bodies – even in virtual spaces. His work has been influential for my own practice because of the way he creates ruptures and unexpected elements that question the “usual” expectations we have of systems (such as Second Life).

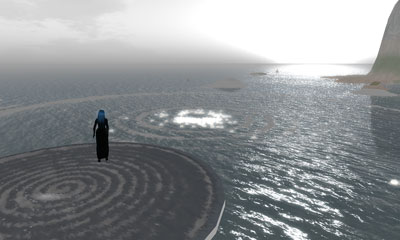

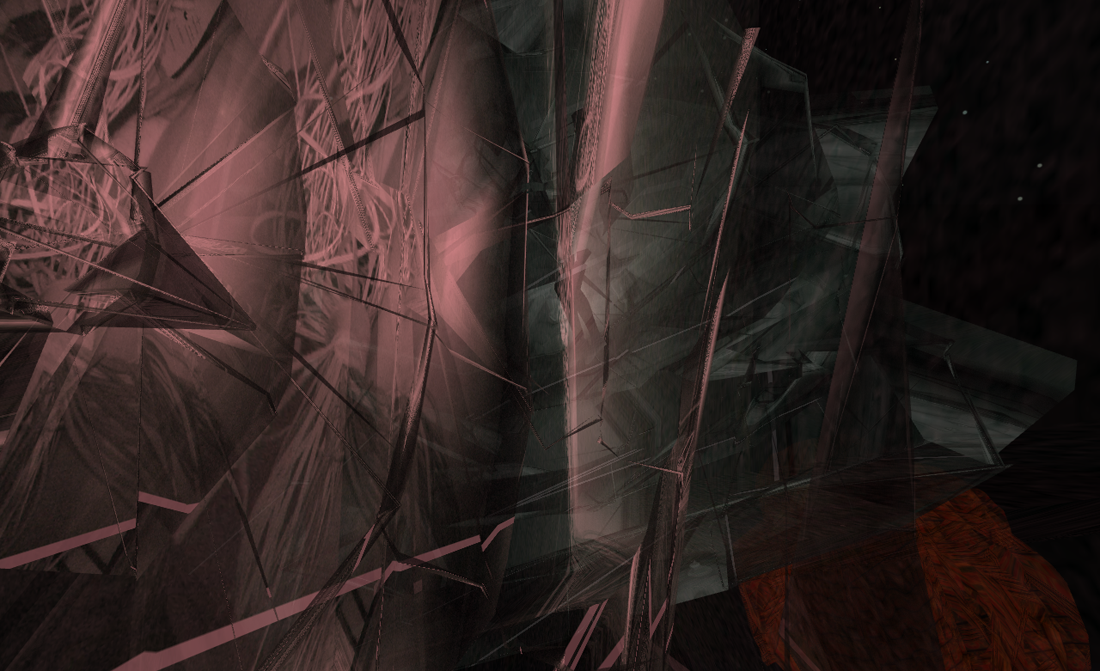

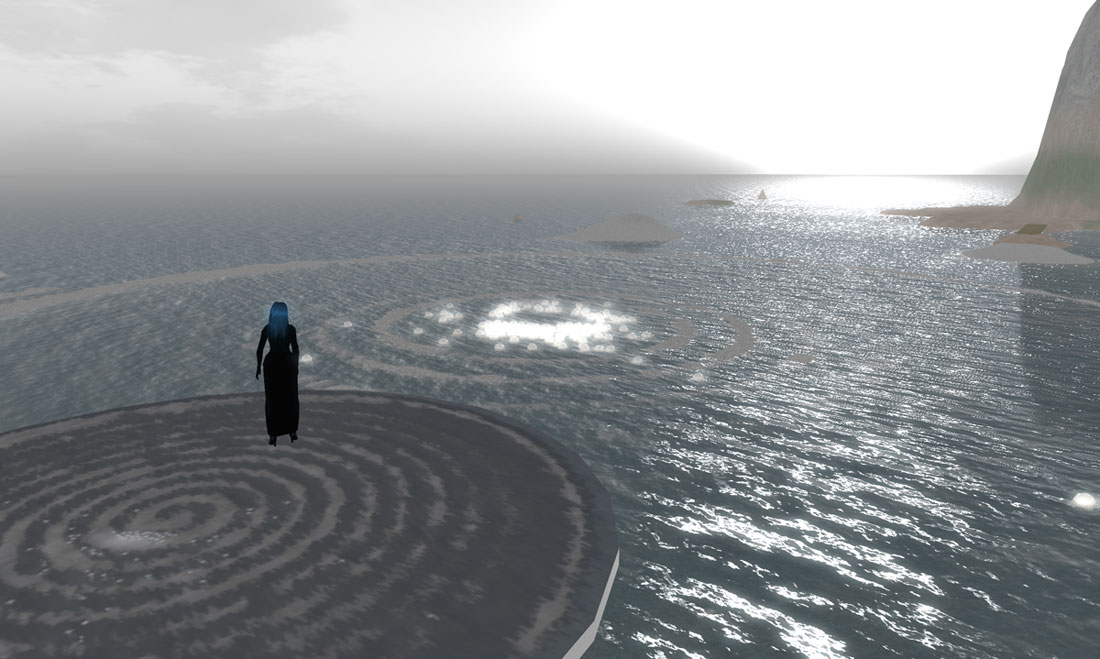

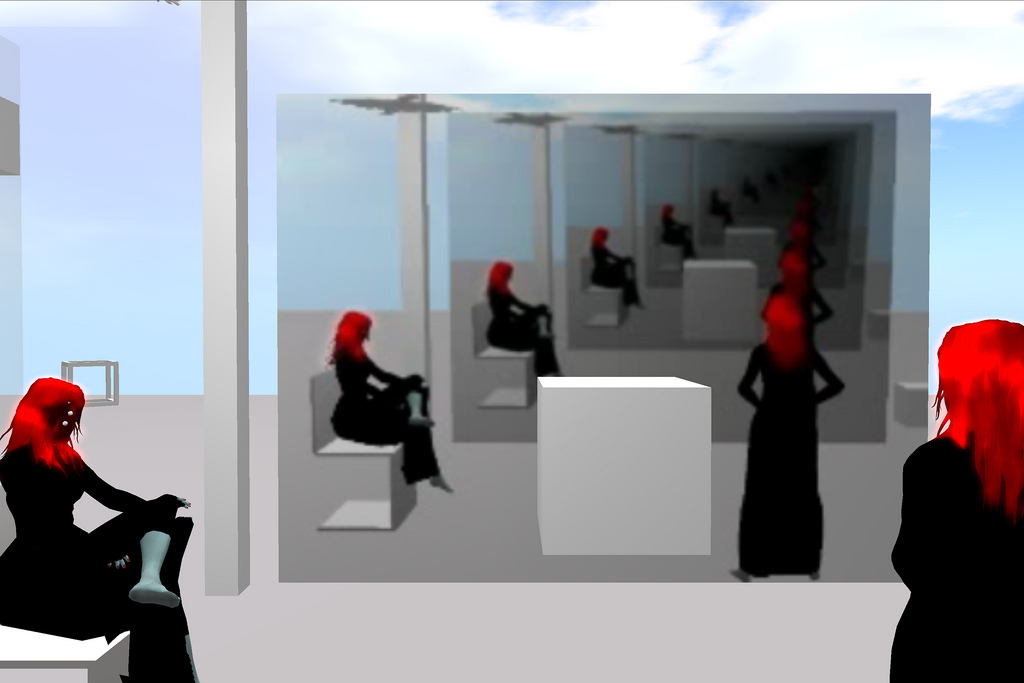

Figure 1.16 “Erasing the Spiral” (Oh 2009) , Figure 1.17 "Into the Past" (Oh 2011) , Figure 1.18 "The Next Day" (Oh 2012)

images captured from Second Life performances by Selavy Oh, (images with permission from Selavy Oh)

(click to view larger images)

Like Sondheim, Selavy Oh uses systems outside of Second life to document aspects of her work – a Blog, a Flickr image "feed", and guest spots on other websites. On documenting her work:

How do you document a performance? Or graffiti on a subway door? Is a photograph or a video sufficient to document it? My work involves participation, and you cannot really document that, you have to experience it. But is an accurate documentation what we really need? What we need is an audience, and if we're lucky, we'll be remembered. (Poid 2009)

Although her installations remain in Second Life for extended periods, her work is mainly performance-based, and requires an audience of avatars to attend and participate in the performances (Figures 1.16 - 1.18). She is also known for collaborations in Second Life – including performances with Alan Sondheim.

Selavy Oh is known as one of the best “builders” in Second Life – she creates content that is specifically designed for the Second Life environment and she uses the elements of that medium, the peculiarities, the glitches and limitations to her advantage. These include buildings that collapse when touched by avatars and time-based elements that change and reform the environment.

The problems and risks of working in Second Life are exemplified by an email that Sondheim wrote to Linden (the company that owns Second Life), which was also copied to the Netbehaviour email list for public scrutiny. In this email, Sondheim asks for assistance to fix a work in Second Life that was damaged through collaboration with Selavy Oh[8]. Because the artwork only exists in Second Life, on the Linden servers, artists are at the mercy of a third party to keep their work accessible.

Capturing images and video is the only way to get content out of Second Life at present. Artists such as Selavy Oh would like to see a more open platform available to artists so that works can be saved elsewhere, or even acquired outside of Second Life – something not possible with the current system. These issues of ownership and control affect many artists working in virtual online environments: we need to find methods of practice that might somehow assist us in minimising the loss of work, or in providing a safe keeping-place for documentation of ephemeral virtual artworks.

Database

The Database is often the underpinning structure for many new media artworks. It may be wrapped in layers of multimedia content, but it forms an important part of this research project: in the development of the Blackaeonium archival system; and also in the creation of many of the artworks developed during the research project. Selected practitioners that work with the database in a similar way have been examined here.The artwork of Martine Neddam exists in virtual spaces and databases. She is best known for creating websites for alternate identities or “avatars”. Her website Mouchette.org has been created for the virtual character Mouchette, a thirteen year old girl. The name Mouchette (meaning little fly) is taken from the 1967 French film of the same name by Robert Bresson. The film depicts the tragic story of a teenage girl who after several traumatic events, drowns herself by rolling down a hill wrapped in a shroud intended for her mother’s funeral.

Figure 1.19 Martine Neddam, Mouchette.org, (1996)

(image with permission from Martine Neddam)

(click to view larger image)

The Mouchette.org website (Figure 1.19) is controversial because one section of the site asks the audience to recommend the ideal “suicide kit” for a teenage girl. Users can submit text to the site, which then forms a part of the ongoing narrative, archive, and assemblage of content. It is interesting to note that Ben Vautier, one of the Fluxus artists created the “Flux Suicide Kit” (which alludes to van Gogh and the myth of the angst-ridden artist).

Some users are aware the Mouchette.org website is an artwork, but others have contributed to the site thinking it is a real thirteen-year-old girl. The collected texts range from insults and hate mail, to clever suggestions for Mouchette’s suicide and sincere, pleading letters offering prayers and assistance. Mouchette.org has been reinterpreted on several occasions as a physical installation in a gallery, and has been shown in various forms since its inception in 1997. This work is relevant to this research because it influenced some of my earlier new media works such as Same Old Dreams, and it’s ongoing, database-driven framework and reinterpretations in different time-space locations echo what I am trying to achieve through the online, database-driven archival system and creative works in this project.

In “Zen & the Art of Database Maintenance” Neddam has written a most eloquent essay describing the too familiar difficulties of being a “net artist”, (Neddam 2010).

Once your webhost went down while you were presenting a lecture about your website at a conference about art on the Internet. Out of desperation you tried to browse your site from your local copy but the pages displayed all the PHP codes instead of the dynamic content. Confronted by all this code and your evident confusion, your audience became really impatient and didn't even believe you really were the author of a virtual character. (Neddam 2010)

This text doesn't offer any solutions, in fact it reveals a plethora of problems in working with variable media arts.

Your database programmer once made a mistake in which the timestamp of your entire database was destroyed. All your users’ entries and all the text in your database were still there, in the right categories, but all under one date: 1.1.1970. This was an incredible disaster, but a very ironic one: you would rather have lost the entire database than just this small ‘piece of time’ […] So, do you have a good automatic back-up system of your own now? To be honest, you don’t really know…. (Neddam 2010)

Neddam’s essay is part of the publication Archive2020: Sustainable Archiving of Born–Digital Cultural Content (Dekker 2010). Archive2020 was assembled by the Virtueel Platform in the Netherlands and contains texts by digital media artists and developers. These texts capture the recent zeitgeist; they give a very accurate account of where we stand now as artists of variable digital media – the problems, the specific nature of these art practices, and most importantly for this research project, they highlight the groundswell of desire by artists to work with archives in a sustainable way to preserve creative digital content.

Lev Manovich’s texts on new media, database, art, cinema and narrative (Manovich 2001), have been influential for many new media artists working with database and networked technologies. He has articulated many problems that are central to the concerns of media arts research such as the importance of the database and metadata as paradigms enabling us to access, manage and find meaning in our multimedia content, which is also important to this research project.

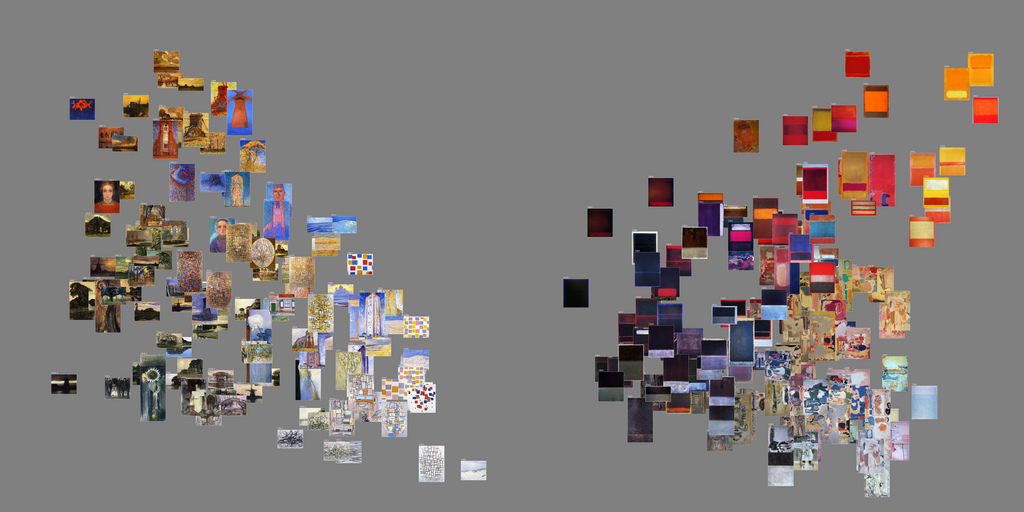

His current major research in the Software Studies Initiative (Manovich 2008a), in the field of “big data” visualisations for cultural artefacts, is now gathering many followers because of the investigation of methods for finding meaning in cultural content through large-scale data visualisation. His recent texts also espouse the importance of understanding our software - the code languages that underlie all of our “transparent” applications, lest we further lose control of our content and autonomy in using digital systems (Manovich 2008b).

Figure 1.20 Lev Manovich, “Mondrian+Rothko.X_brightnessMean.Y_saturationMean.images” (Manovich 2011),

(image with permission from Lev Manovich)

(click to view larger image)

The ideas posited by those working with “big data” like Manovich and his colleagues, are interesting because they are leading to the development of re-interpreting artworks (on a large scale) using automated processes, deriving different kinds of information and meaning from artworks within a continuum. One can see the outcomes in still image and video derived from working with art, film and video data visualisations on a large scale such as “Mondrian vs Rothko” [9] (Manovich 2011) (Figure 1.20).

The work of the Software Studies Initiative, although very different from the work undertaken in this research project, is relevant because it brings together collections of artworks, using metadata or metacontent to analyse artists’ practices across a space-time continuum. The database is the tool required to assemble the information and present it in different ways - the Blackaeonium archival system uses database in the same way.

Remix

The critical aspects of Remix that apply to digital media are:

- the ability to cut/copy and paste content without destroying the original item, thus creating a continuum of creation through loops and sampled content - “the spectacular aura of the original”(Navas 2011a) remains intact (which Eduardo Navas lists as a requirement of the remix);

- the concept of Allegory – using the authority of pre-existing material to locate the remixed work in a continuum of art history; the propositional nature of the remix artwork that raises questions about the status of the artwork as “object” and the nature of the creative act (the changing definition of the “author”); and

- the “Meta” of the remix - the remix is a reinterpretation that refers to other works, creating a trace – possibly reflexive in some cases, which is evidence of a continuum of creative practice.

the remix artist is not only preserving a record of culture for future generations, but also for those of the past. (Harley 2009)

In the context of this research, Remix theory has been investigated, with a focus on the meaning of “remix” for variable, multimedia artworks, informed by the history of remix in music. Although current remix theory is broad in nature and encompasses a range of cultural practices, it is important to this research project because the way artists work with remix in an online digital archival assemblage, addresses the critical aspects of Remix as listed above.

The above creative projects and texts do, I believe support my theory: that remix can be a method of preservation. While the works of those outlined above do this quite explicitly I am arguing further that remix is what artists do, whether explicitly or implicitly in their practices and processes.

As artist and theorist Eduardo Navas states:

The contemporary artwork, as well as any media product, is a conceptual and formal collage of previous ideologies, critical philosophies, and formal artistic investigations extended to new media. (Navas 2010)

Recognising this may be the best way to engage artists to adopt preservation strategies into our work.

Navas hosts a website “Remix Theory” (Navas 2012), which is a portal for accessing his remix artworks, research and texts, and provides links to other related artists and theorists. Navas’ definition of the types of remix (Navas 2011a) are based upon his own artwork and research that begins with a history of remix in music of the late twentieth century, and continues with the inclusion of art and digital media practices in popular culture and academia.

The Regenerative Remix is exposed in the activity of constant updates made with software that also creates a well-organized archive; the Reflexive Mashup has been the case study in this occasion. Yet, even when its archive may be accessible, it does not mean that people will necessarily ever use it directly; most people will stick to the most immediate material, placed on the front pages of any online resource […] The database becomes a delivery device of authority in potentia: when needed, call upon it to verify the reliability of accessed material; but until that time, all that is needed is to know that such archive exists. (Navas 2010)

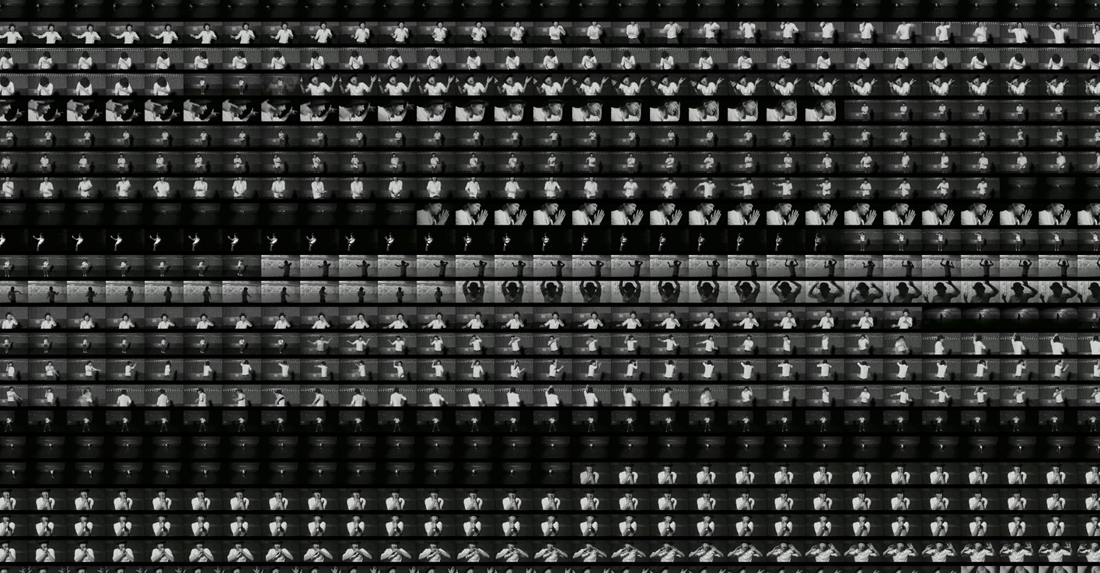

Navas’ artworks and research projects investigate phenomena such as the “YouTube Remix” (Navas 2011c), where multiple users “author” remixed videos based on popular content. This process is also known as “mashup” and “culture-jamming”. These videos are posted to YouTube and create a continuum of reinterpreted video. Examples Navas discusses in his texts include the Radiohead “Lotus Flower” music video remixes (Figures 1.21 & 1.22). These are examples of remix in a new media context.

This type of "collage" that makes new media work possible is completely dependent on sampling, […] sampling is the essence of Remix. (Navas 2006)

Figure 1.21 & Figure 1.22 Eduardo Navas, “Radiohead Lotus Flower YouTube Remixes”, (Navas 2011c), (Navas, 2011d)

(images with permission from Eduardo Navas)

(click to view larger images)

These Remixes (created by various “authors” from the YouTube audience) use the original Radiohead video clip - a black and white video with long-takes that shows Thom Yorke dancing in a singular and frenetic style throughout the video. The authors cut, copy and paste sections of the video – in some cases remixing the sampled visual content with other music tracks such as the “Macarena”, or mix the video with fast moving music in different styles to show Yorke dancing in an increasingly crazy fashion – often to humorous effect. Navas has used the tools of the Software Studies Lab to create visualisations of these remixes, showing patterns and flows of data as can be seen in Figures 1.23 and1.24. These visualisations by Navas form their own reinterpreted artworks.

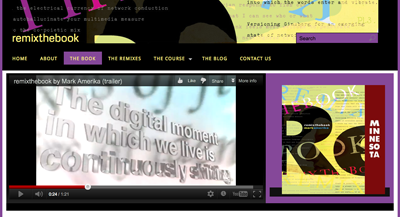

Figure 1.23 Mark Amerika, “Remix the Book” 2011

(image with permission from mark Amerika (Amerika 2011a))

(click to view larger image)

Mark Amerika is a significant figure in both new media art and remix art[10], with widely recognized online interactive works like Grammatron (Amerika 1998) and Filmtext (Amerika 2002). Most recently, the artwork/text/publication “Remix the Book” (Amerika 2011a) has become a significant project that reflects current remix practice. Remix the Book (Figure 1.23) is itself a remix of media, and Amerika invites others to take his work and create further remixes from it. These remixes, as with the work in this research project, also spill into the “tiered” media of blogs, guest twitter feeds, and other online and physical publications and artworks. Remix the Book embodies the proposition under examination in this research: that remix is something that artists naturally engage in:

The concept of novelty or more specifically novelty generation as the modus operandi of all living creatures mutating in the remix pool relates to current trends in networked art where the artist-as-medium postproduces the Source Material Everywhere as part of a larger co-poietic unfolding inside the networked space of flows. (Amerika 2011b)

This recent proliferation of remix culture and contemporary art is not an innovation, but a concentration of creative practice that has been enabled by digital technologies that make remix, mashup, recombination, copying and cut-and-paste so easy to perform.

Variable Media Preservation: a brief outline of the search for a strategy

A variety of preservation initiatives were investigated to find strategies that might be complementary or suitable to the intended research project development. While many of these initiatives are undertaking essential work in the preservation of digital media, and there is much to learn from their methods, suitability for artists in the studio is the element missing from the processes and systems developed.

The initiatives that work most closely with artists are the ones mentioned in the Introduction: the Variable Media Network, the DOCAM Research Alliance and the Rhizome.org Artbase. Other projects investigated include:

- The Australian Centre for the Moving image (ACMI 2012);

- The Australian Women’s Art Register (2011);

- Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (2005);

- The many projects initiated by the Records Continuum Research Group founded by Frank Upward and Sue McKemmish at Monash University (RCRG 2006)[11];

- The Contemporary Art Archive at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA 2012) Sydney;

- Digital Lives Research Project >> An Initial Synthesis (John, J.L. et al. 2010);

- ERPANET - Electronic Resource Preservation and Access Network (2006);

- InterPARES projects 1, 2 & 3 (InterPARES 2012);

- La Fondation Daniel Langlois (2006);

- PADI (Preserving Access to Digital Information) (National Library of Australia 2006a);

- PANDORA, Australia’s Web Archive (National Library of Australia 2006b);

- PANIC (preservation webservice architecture for newmedia and interactive collections) (2007), MAENAD Group, University of Queensland;

- VERS (Victorian Electronic Records Strategy) (2007), Public Record Office Victoria.

This research included the search for artist-led initiatives that are attempting projects and strategies similar to the Variable Media Network Initiative and the DOCAM Research Alliance, but on a smaller, more personal scale – without institutional involvement. Despite not being able to find a project unattached to a gallery or network of cultural organisations, the Variable Media Questionnaire (VMQ) (Forging the Future 2012) and other tools developed by Jon Ippolito, Richard Rinehart and others from the Variable Media Network and Forging the Future come closest in intent to the type of initiative being sought.

With regard to theory of preservation strategies, the paper by Richard Rinehart (2003) on formal notation for variable media has been significant in the field of preservation because it promotes the idea of reinterpretation of works as a method of preservation. This may be influenced by the musicians and composers that formed part of the Fluxus network (works that Rinehart and others are now seeking to preserve) where scores for performances were published, thus preserving the essence of an ephemeral performance work, and allowing others to interpret the work as one would a music score or script for a play.

Reinterpretation is a dangerous technique when not warranted by the artist, but it may be the only way to re-create performed, installed, or networked art designed to vary with context. (Rinehart 2003)

The Variable Media Network Initiative matches artists with collecting institutions for the purposes of preserving complex new media artworks. Organisations involved in this initiative include the Guggenheim Museum, The Daniel Langlois Foundation and the Still Water New Media Program (Still Water 2012). The Variable Media Questionnaire (VMQ) developed as a tool for documentation, places a high level of importance on the artist and other stakeholders documenting an artwork, and stating how they think the artwork should be accessed and preserved over time.

This Questionnaire is unlike any protocol hitherto proposed for cataloguing or preserving works. It requires creators to define their work according to functional components like "media display" or "source code" rather than in medium-dependent terms like "film projector" or "Java." The variable media paradigm also asks creators to choose the most appropriate strategy for dealing with the inevitable slippage that results from translating to new mediums. (Forging the Future 2012)

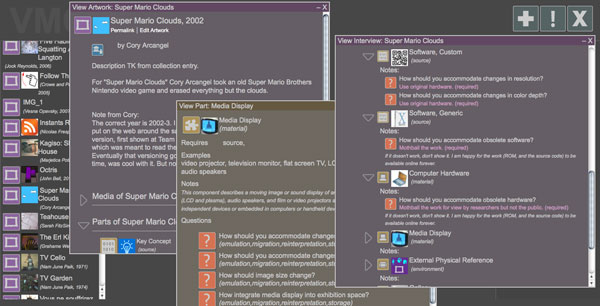

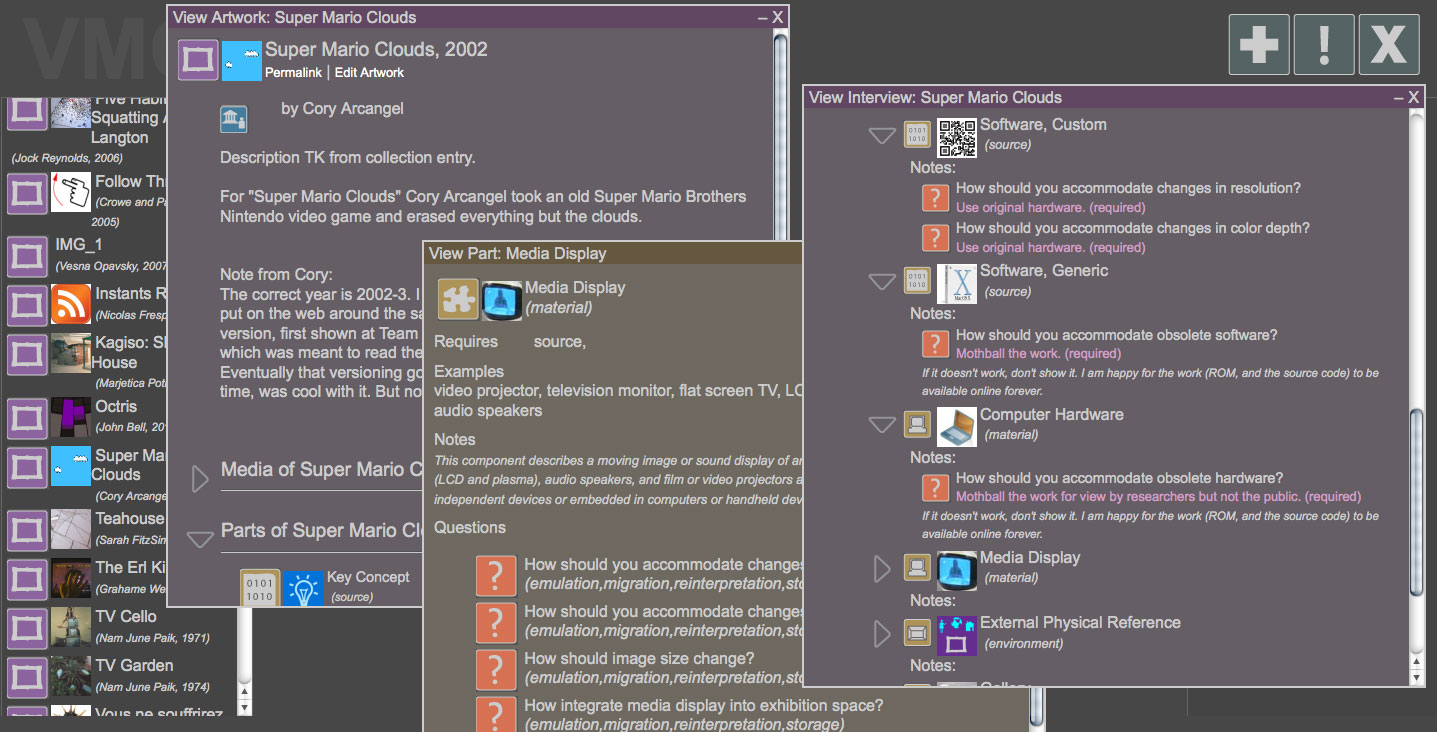

One variable media case study that has been documented with the VMQ is Cory Arcangel’s “Super Mario Clouds”(Arcangel 2002). This work is a remix, and a “hack” of the Nintendo Game “Super Mario Brothers". Arcangel uses old media like Nintendo games cartridges, and alters them to create new media - in ways not intended by Nintendo such as breaking into the cartridge to access the chip. This work only shows a continuous looping animation of white pixelated clouds scrolling across a flat blue sky. All other elements have been removed from the game. To see exactly how Arcangel made the work, and to view a reinterpretation of the work as a YouTube video, Arcangel’s website (Arcangel 2002) contains full documentation of the project from images of the original cartridge, to instructions for others to create their own versions with old games cartridges.

Figure 1.24 Image capture of the Variable Media Questionnaire Demo showing documentation of Cory Arcangel’s work “Super Mario Clouds” (VMQ 2012)

(image with permission from Jon Ippolito)

(click to view larger image)

The VMQ holds descriptive information about the artwork, the source code, the media used in installation (Figure 1.24), and it also documents interviews with Arcangel where he outlines his intentions for how the work should be exhibited, in particular, the limits of reinterpretation – how far can the work be altered before it is not acceptable to the artist? For example, when asked “How should the installation change dimensions?” Arcangel responds:

If I'm alive, please call. I ALWAYS do this differently, depending on the space and available equipment. If I'm not alive, you must do it exactly the same way as it has been done in a previous version, including the dimensions of the space.

(VMQ 2012)The VMQ allows the artist to be specific about what is acceptable and what is not when it comes to future representations of the work.

Ippolito and his colleagues at Forging the Future and the Still Water New Media Program have also developed a tool to facilitate interoperability between systems and cultural organisations. The Metaserver (Forging the Future 2012), “points to instances of particular works across cultural organisations, as they transition from one version, medium, or context to the next”. The Metaserver is a project that addresses the current situation where cultural organisations are all working with different standards, datasets and systems for documenting artworks. Rather than trying to implement one universal standard, the Metaserver works in the manner of a semantic search engine, to locate collections using minimal descriptive metadata.

The the outcomes reported by the Clever Recordkeeping Metadata Project (RCRG 2006) at Monash University share this view that tools for interoperability are required to deal with the actual situation that exists between groups and organisations that need to share information. We are not yet ready for a unified standard, and perhaps this is something that will never be possible, or at least will be difficult to achieve because each cultural organisation has its own specific requirements. Furthermore, the artworks requiring documentation are difficult to classify with one universal standard.

Rhizome.org (2006) is a major entity in the world of new media arts, net.art, database art, and many media arts forms using digital technologies. The name “Rhizome” comes from the Rhizomatic structure of the Internet, and the philosophical discourse on the Rhizome by theorists such as Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. Discourse on rhizomes has been influential to many developers of new media projects.

the rhizome pertains to a map that must be produced, constructed, a map that is always detachable, connectable, reversible, modifiable, and has multiple entranceways and exits and its own lines of flight.(Deleuze & Guattari 1987, p. 21)

Rhizome.org initiates many programs that deal with “the creation, presentation, discussion and preservation of contemporary art that uses new technologies in significant ways” (Rhizome.org 2006). Rhizome.org has also been influential in developing strategies for creative access to their Artbase archive via many experimental interfaces by commissioned artists to investigate ways of interacting with the Artbase, and ways of visualising the content within the archive. The work undertaken by those involved with Rhizome.org has been influential in this research project. Chapter 2 discusses how the Rhizome.org Artbase interfaces played an influential role in the development of the Blackaeonium archival system.

In 2011, Rhizome published a text titled Digital Preservation and the Rhizome Artbase, (Fino-Radin 2011) outlining their policy for and implementation of variable media preservation practices. This work is directly related to their involvement with the Variable Media Network Initiative, the strategies and tools used by Rhizome.org have been developed through this network in conjunction with other cultural organisations such as the Forging the Future group.

The DOCAM Research Alliance case study “Nam June Paik, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 1989” (DOCAM 2010) is an example of a significant variable media artwork requiring an ongoing preservation strategy due to the nature of the technology used (Cathode ray tube screens and analogue video within an installation structure). The documentation on the DOCAM website for this artwork highlights the issues that many of us working with variable media face – obsolescence and degradation of formats, issues relating to the preservation strategies available (such as migration or emulation), and the ethical problems that come from trying to preserve the artist’s intent for how the work should be viewed (if, as in the case of Nam June Paik's work, the fragile cathode ray tubes and analogue video tapes cease to function).

The documentation in the DOCAM system discusses these issues, and lists possible options for migration or emulation of the analogue video media and attendant hardware. The question is, would the work be very different if digital screens and software were used to display the moving image content within the physical structure? Unfortunately, Paik was not consulted about these preservation issues before his death in 2006, so his intent for future reinterpretations of his work is unknown.

It’s difficult to know if the properties of digital video presentation will be a valid form of emulation and migration to enable the work to remain accessible. The quality of analogue video and old cathode ray screens create a certain type of light, and a certain type of flicker and glitch – the resolution and compression, the way the colour information is fed to the screen is different to digital video and LCD screens. Could it be similar enough though, for the audience to access and engage with the work in the same way? Paik is thought to be the first video artist, so it is crucial to maintain the artwork in a way that represents the authenticity and integrity of the work. It will be left to the current custodians and stakeholders to conserve and preserve the work whilst attempting to deal with the artist’s intent in an ethical and respectful manner.

It was concern for these issues of artists’ intent that formed part of the impetus for undertaking this research project. If artists’ intentions are documented and well known, it will be easier for other stakeholders to manage and maintain variable media artworks in an ethical manner.

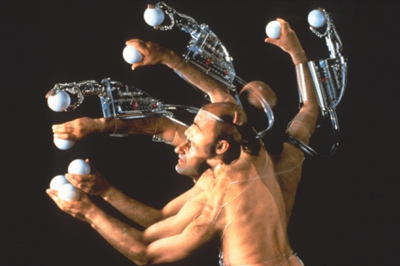

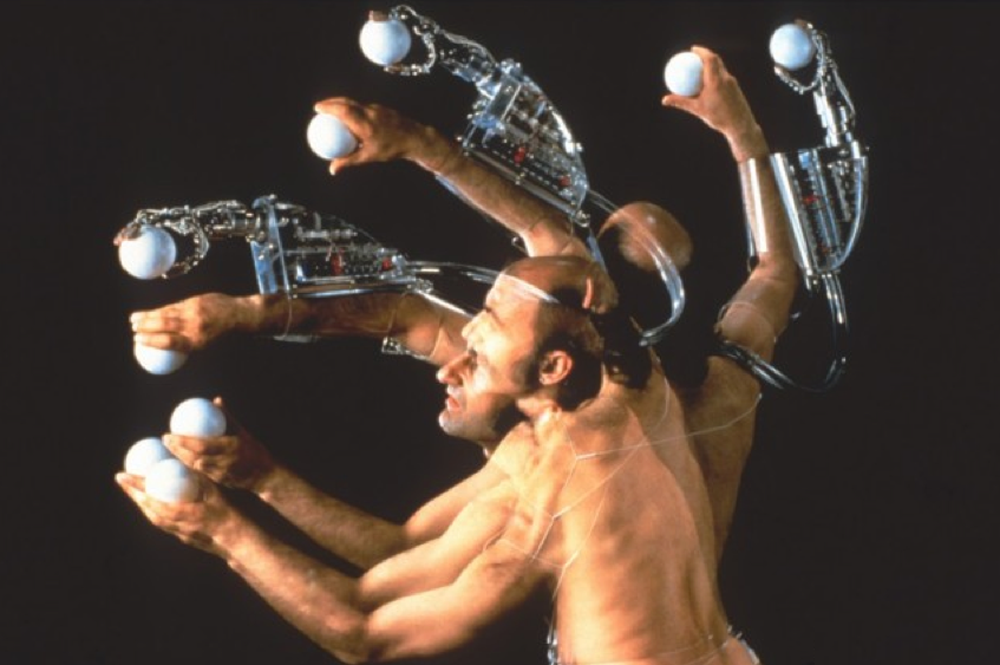

InterPARES is an international initiative that has examined “the creation and maintenance of accurate and reliable records and the long-term preservation of authentic records in the context of artistic, scientific and government activities that are conducted using experiential, interactive and dynamic computer technology” (InterPARES 2006). Project 2 of the InterPARES collaborative initiative has published a number of research outcomes. Amongst these outcomes are case studies examining the way creative practitioners create and maintain their records. Three of these case studies were investigated for this research project (Case Study 02: Performance Artist Stelarc; Case Study 10: The Danube Exodus; and Case Study 15: Waking Dream). The most relevant of these is the case study for the artist Stelarc (a significant Australian performance artist who uses his own body as the medium of his art) (Stelarc 2012), although all three case studies involve variable media with reinterpreted works developed across a continuum of creative practice. Interestingly, The Danube Exodus case study made reference to the Variable Media Initiative (although the artists involved had not sought to implement any actual strategies recommended by that initiative).

While the analysis of Stelarc’s records generation and management practice was comprehensive, and showed (what one might say is true of a lot of artists) that there is no structured method of capturing, organizing and preserving content other than the most important content (according to Stelarc) being placed on a website, the fact that Stelarc regards his own body as the most important record of his art practice was not dealt with in a way that would be meaningful to the artist. It was documented in the case study, but no attempt has been made to suggest how artists (who create content in ways that cannot be encompassed by the usual archival methods currently used in the field) might even begin to deal with the complexities of variable, and even organic media artworks (Figure 1.25).

Figure 1.25 Stelarc, Multiple Hand, c1998 (Stelarc 2012)

(image with permission from Stelarc)

(click to view larger image)

This kind of recommendation was not within the scope of the InterPARES 2 project, therefore, I was anticipating that InterPARES 3 would take this research further and look at possible models for artists. This has not happened thus far. None of the InterPARES 3 projects deal with artists’ records or engage with issues relating to artists. When I contacted the InterPARES group about this issue, they directed me to the DOCAM website.

The research that exists in the field of digital media preservation recognises the problems of complex media preservation and access, but no one yet has a solution that could become a standard or general recommendation other than to document ephemeral artwork in “standard” digital formats, for image, video, audio and documents, and then treat these documentations as we would any other type of record. Preservation strategies at present appear to be emerging from analysis of case-by-case projects by cultural organisations that attempt to do the best they can to ethically deal with the artwork and the artist.

This research project is attempting to at least partially explore the many gaps in dealing with content developed by artists. This is being done by working at the studio level from the inception of creative projects to try to deal with the issues identified by research in the aforementioned institutions and organisations.

Current theories of archiving

Upward’s Continuum Model

I have based the premise of this research on artists working with an archival continuum to inform our creative practices and to future-proof our work. The rhizomatic new media work, and the archival continuum can be merged, perhaps recombined or remixed to form a useful tool, process or methodology for artists.

Frank Upward’s article “Continuum Mechanics and Memory Banks (1) Multi-polarity” (Upward 2005) is an important text that crystallises much of the underlying ideas for this research, and would be useful for artists to understand – in particular the multiplicities and complexities of creating the archive. Upward identifies elements of the continuum such as “relational continuity” and “a blurring of separateness of individual points”, and transformative changes that produce new content (remix). Most importantly he discusses the dimensions of the continuum in space-time. Of elements that define the Continuum, Upward includes:

Changing notions of time which in the twentieth century have moved from Minkowski’s four dimensional view of the spacetime continuum towards multi-dimensional approaches such as Bergsonian conceptualizations which can include four dimensions of time (past, present, future and ‘becoming’), and which accept there are billions of points spatially and temporally from which one can trace movements out from time’s multiple surfaces. (Upward 2005, p.87-88)

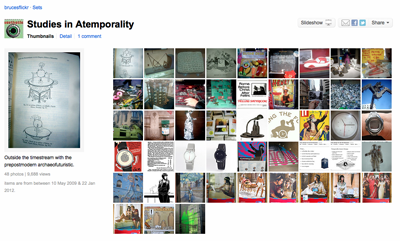

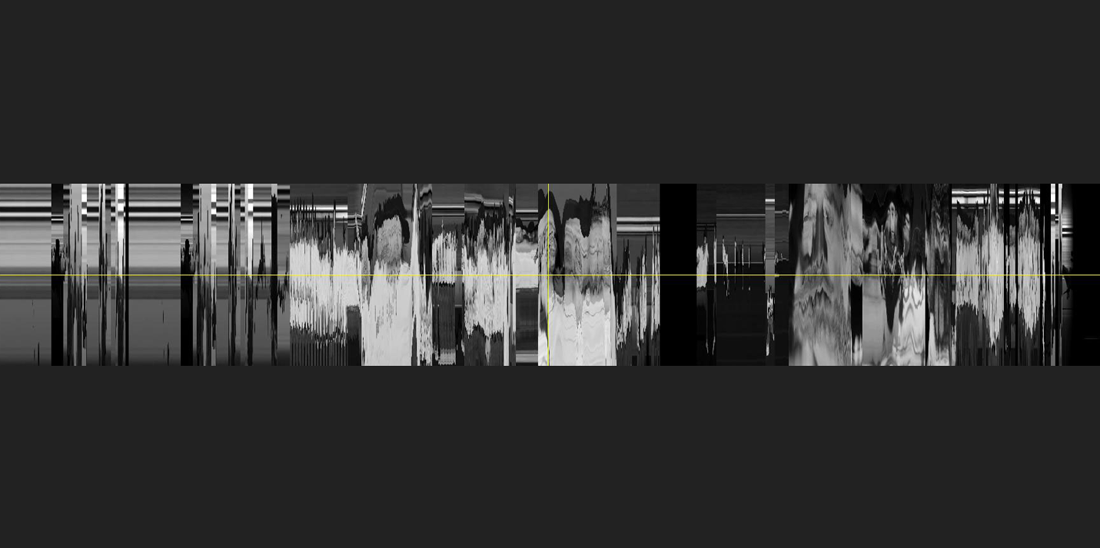

Upward uses the term “spacetime distancing” (Upward 2005, p.87) as a synonym for archiving. This term shares a conceptual space with the term “atemporality” that has become part of the recent discourse in media arts, mainly due to Bruce Sterling’s keynote address at the Transmediale Conference of 2010 titled “Atemporality for the Creative Artist” (Figure 1.26):

Refuse the awe of the future. Refuse reverence to the past. If they are really the same thing, you need to approach them from the same perspective. (Sterling 2010)

Figure 1.26 “Studies in Atemporality”, Bruce Sterling’s Flickr Feed (2012)

(image with permission from Bruce Sterling)

(click to view larger image)

Upward also discusses "recursive cycles of creation" (in relation to mysterious beginnings and M theory). The remixed archive is a representation of that Bergsonian conceptualisation of time. The archival assemblage contains past artefacts, present representations of content, future possibilities for generating new work, and is in a constant state of becoming.

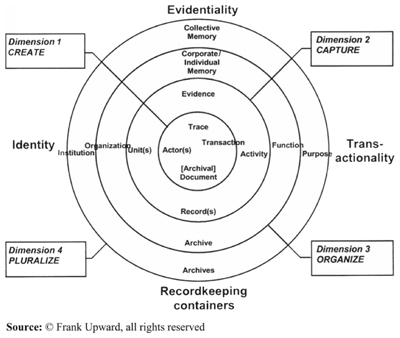

The (Archival) Records Continuum Model (Upward 1996) advocates the use of systems and methodologies to enable access to records (objects) across space and time.

A continuum-based approach suggests integrated time-space dimensions. Records are 'fixed' in time and space from the moment of their creation, but record-keeping regimes carry them forward and enable their use for multiple purposes by delivering them to people living in different times and spaces. (SAA 2004)

This has meaning for how we create artworks and how we might deal with our variable media objects and the content contained within. Artists must investigate methods for being proactive and not reactive about preservation – to consider preservation at the beginning of the creative process, not just rescue what remains at the end of a process. If we see archives as active, not passive, and as “sites of power” (Cook 2000), then preservation should be incorporated into creative processes for working with variable media objects.

We need to move the entire system of digital production from material being “born digital” to being “born archival”, which is to say created with the attendant metadata and format definitions attached or readily discoverable. (Shirky 2005, p.43)

The concept of “born archival” artwork is one we variable media artist should adopt because it is an important conceptual basis for incorporating archival and preservation strategies into our artworks from the point of creation: not just for digital works, but for works of all media whether analogue, digital or mixed variable media.

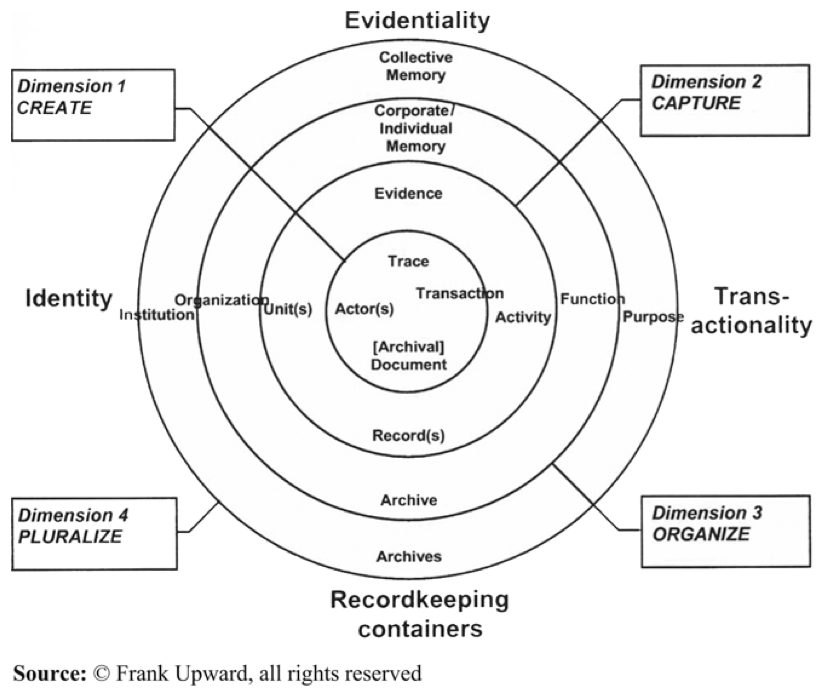

To summarise the four dimensions of the continuum (Figure 1.27):

- 1D Create: the actors who carry out the act, the acts themselves, the documents which record the acts, and the trace, the representation of the acts.

- 2D Capture: systems that capture documents in context in ways which support their capacity to act as evidence.

- 3D Organise: the organisation of recordkeeping processes, the manner in which a body or individual defines its/his/her recordkeeping regime, and in so doing constitutes/forms the archive as memory of its/his/her functions.

- 4D Pluralise: the manner in which the archives are brought into an encompassing (ambient) framework in order to provide a collective social, historical and cultural memory.

Dimensions summary based upon descriptions from McKemmish & Upward (2001)

Figure 1.27 Upward's Continuum Model (Upward 1996)

(image with permission from Frank Upward)

(click to view larger image)

The continuum model best describes contemporary institutional recordkeeping practice, although much of the theory in the four dimensions can be used for personal archiving, or for records and artefacts that are created through creative practice.

Digital media are crucial to this interpretation of the continuum as the mechanism and the (ambient) framework that allows us to capture objects, manage them and make them accessible. The ambient framework is more than a means for pluralisation. It also provides means to organise and reorganise the content – the remix.

The continuum model also encompasses movement across space and time, recognizing that archival records and their metadata are continually shifting, transforming, and gaining new meanings, rather than remaining fixed, static objects. (Cook 2000, p.11)

These layers and continuum dimensions are blurred in current web technologies. In this interpretation of the continuum, to organise could also be to create within the context of recombination and remix of content. Pluralisation as distribution and proliferation of content through an ambient framework, the user’s agency with that content, and the cultural implications for that content, affects all dimensions of the continuum model through space and time.

Discussions about personal archiving practices

Significant research in archival theory has taken place here in Australia. Specifically, the research and writings of Sue McKemmish and Frank Upward, in relation to personal archives, the records continuum model, and the Records Continuum Research Group that they established at Monash University (RCRG 2006).

When investigating personal archiving practices, the paper “Evidence of Me…” by Sue McKemmish (1996), subsequent response by Verne Harris “On the back of a tiger: deconstructive possibilities in “Evidence of Me…” ” (2001), and response to Harris’s paper by McKemmish and Upward, “In Search of the Lost Tiger by Way of Sainte-Beuve: Re-constructing the Possibilities in “Evidence of Me...” ” (2001), presented a discourse that focuses on considerations relating to personal archiving, witnessing the cultural moment, and how we artists might affect our own creative endeavours through self-documentation[12].

McKemmish, Harris and Upwood do not specifically discuss digital media artworks in these papers, nor the creation of multimedia artistic content as personal archiving or witnessing. It is also important to note that these papers all predate the blog explosion. Despite this, their discourse has currency in the present environment because they discuss methodologies that can readily apply to the personal digital archives being created today.

It is necessary to acknowledge “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression” by Jacques Derrida (1996) as it forms part of the discourse by McKemmish, Upward and Harris, but also because it raises certain issues relating to the archive and “destruction drive”, and ideas relating to memory (and forgetting) that many artists address.

the technical structure of the archiving archive also determines the structure of the archivable content even in its very coming into existence and in its relationship to the future. The archivization produces as much as it records the event. (Derrida 1996, p.17)

In undertaking this research, what first seemed for me personally to be a gulf between the philosophy and theory surrounding the “Archive”, and archival practice at the “coal face” (what we archivists undertake in our work on a daily basis), has now started to converge in the development of this research project. What I have found is that ideas such as Derrida's: “the archivization produces as much as it records the event”, actually mean something to the artist in working with the archive as a part of creative practice. To the artist, it becomes clear that creating an archive also creates something new, something more than the documentation of “records” and artefacts. Being able to use the archive to develop new creative works is an actualisation of the concept of archivization as artwork.

The texts of a few other notable and internationally recognised archival theorists that have been influential in the field of archival science, and also have much to contribute to creative practice, were investigated as part of this research. The Canadian Archivists David Bearman (1999) and Terry Cook (2000), and also Eric Ketelaar (1999) from the Netherlands, are significant and relevant for their theories on archival constructs, practices, methods and preservation of cultural heritage.

Ketelaar and the shifting of meaning in the Archive

Every interaction, intervention, interrogation, and interpretation by creator, user and archivist is an activation of the record (Ketelaar 2001), each in a new ‘concept space (Ketelaar 2012)

Ketelaar’s texts elaborate his theory of “archivistics”, which is his term for the more inclusive approach to archiving that deals with all dimensions of the continuum from a cultural and social perspective. This is particularly relevant to the creative content developed by artists, as we need an approach that treats our records, artefacts and artworks as having archival potential from the point of creation – the first dimension of the archival records continuum.

Ketelaar’s most recent text “Cultivating archives: meanings and identities” Archival Science, Vol 12 (Ketelaar 2012), discusses meaning in and from the archives using cultural and artistic examples to illustrate his theory. One particular example is the Women’s Suffrage Petition of 1891 from Victoria, Australia – also known as the “Monster Petition” because of its size (Parliament of Victoria 2010). This record/artefact is held by our own Public Record Office (PROV) here in Melbourne (Figure 1.28). The petition contains signatures from almost 30,000 women from Victoria, Australia. The original sheets with signatures have been pasted to a roll of fabric, making an impressive “scroll” – the original intent would have been to make a sensational statement by unrolling the petition in parliament.

Figure 1.28 The “Victorian Women’s Suffrage Petition”,VPRS 3253, Original Papers Tabled in the Legislative Assembly,

1891 Victorian Women's Suffrage Petition (PROV 1891) (image courtesy of the Public Record Office of Victoria)

(click to view larger image)

The significance of this artefact is partly due to the fact that Australia was the first country to give women the right to vote, and to stand for parliament (in 1901). The meaning of the artefact has shifted and changed over time: it is evidence of the women that signed the petition; it is a record that may have influenced an important parliamentary decision; and it is a symbol of the suffrage struggle for women’s rights (and is now listed in Australia’s Memory of the World Register). There may even be other meanings: perhaps it is also an object – a kind of artwork that requires installation, or reinterpretation to be presented to a new audience[13]? Lastly the petition also becomes a reinterpretation through digitisation of the contents - a searchable database now exists for users to find the names of ancestors that signed the petition.

In its current fragile state in the PROV archives, the Monster Petition cannot easily be read as primarily intended (it exists in a customised Perspex case, on a spool (see Figure 1.31), but its meaning and power as an object has not diminished over time. This kind of symbolic record/artefact may be viewed as an artwork that might also have these different stages of currency and multiplicities of meaning over time. The archive, through interaction and interrogation, allows for the content to have different readings and interpretations whether literal or symbolic. That content may become something beyond the original intent of the creator.

“Archives in the Wild”: current research addressing non-institutional archival practices

The idea of the archive as a site of power has meaning for individual artists and small groups working with databases and networked technologies. Simon Pockley’s paper on an “Archival Commons”(Pockley 2005) refers directly to this through its discussion of ubiquitous networks and a post-custodial archival environment, recognising that this is something already happening with the advent of blogs, wikis and other individually (or collectively) motivated and managed websites documenting evidence of me and evidence of us.

The social connectivity of an Archival Commons returns the notion of an archive to our collected ‘non-official’ memory - outside the control of the governing institution. Even though social connectivity is disorderly and unreliable, a digital archive needs to be considered as a conscious space for the imagination where we can enjoy a capacity to aspire rather than be anxious about it being a bureaucratic instrument of control. (Pockley 2005)

By creating lots of small stories in an Archival Commons, Pockley suggests that we could be collectively accumulating a bigger, more diverse story than the one created by institutionalised archiving practices, or collecting many differing stories that could all exist at once – an idea that influenced development of this research project from the beginning.

There are some relevant questions posed by McKemmish and Upward that should be considered in regard to an Archival Commons and were also influential in the development of this project:

what is the significance of bearing witness to the cultural moment to the construction of individual identity;

what role does personal recordkeeping play in forming collective identity and memory;

what is the role of personal recordkeeping in our society and the ‘place’ of the personal archive in the collective archives;

how can we understand recordkeeping as a social system;

how do recordkeeping processes and systems become institutionalised in our society; and

what are the functional requirements for Postcustodial archival regimes that can ensure that a personal archive of value to society becomes an accessible part of the collective memory?

(McKemmish & Upward 2001)This research endeavours to address those questions relating to personal and collective cultural identity through creative work developed in this project, utilising web technologies to create a non-institutional archival space.

New roles are forming exponentially through the use of web technologies in an archival commons. As users we are creators and administrators of our own sites, but also “commentators” and “voters” on the sites of others, linking, “liking”, commenting and referencing content held in multiple sites – tiered works held in multiple locations with multiple points of entry - witnesses to these documented cultural moments.

The Digital Lives Research Project was a British initiative, the aim of which was “to explore a wide range of aspects of digital lives and the curation of personal digital archives” (John, J.L. et al. 2010). The report contains some pertinent statements relating to personal archiving, creative practitioners and content – especially those relating to “archives in the wild”:

Effective, versatile and robust personal information management (PIM) can be expected to emerge in time as demand for efficient handling of personal information mounts; but at present such a comprehensive capability is sorely missing. There is a specific need to promote an archivally-oriented form of PIM that embraces the entire information life cycle, and is directed at securing authentic personal digital objects and making them readily available for use and reuse by the individual creators and owners beyond the immediate future. (John, J.L. et al. 2010)

This research also echoes the findings of other initiatives, highlighting the lack of tools for non-professional users. The general set of recommendations for all individuals that create digital content is useful to artists because of our use of “tiered” methods that place creative content in a range of online systems.

Publications such as Archive2020, the InterPARES 2 research outcomes and the Digital Lives report, are a call to action for the development of new methods, processes and practices for artists. An artist-led initiative is required to identify what artists need.

A key need will be an advanced form of archival personal information management geared to the whole lifecycle that makes it possible for people to grow sustainable personal archives based on continuing use and reuse of their contents and good digital preservation practices. (John, J.L. et al. 2010, p. xvii)

Our “archives in the wild” are increasing in number, and exponentially building a rhizomatic web of links. We now require improved tools to assist with managing this proliferation of content and relationships.

Conclusion

The artists selected for this review demonstrate the continuum of creative practice that uses assemblage, remix and archives to form recombinant poetics in physical and virtual space-time. The scholars now dealing with the works developed through these processes have many challenges to face.

In the convergences of these fields of practice, Steve Deitz highlights the gaps where artists are clearly missing out on the benefits of research and development into archives and preservation of variable media by cultural organisations because the scope for this type of project is so narrow – for whatever reason, be it financial, political or social. As he suggests:

The Guggenheim is focused on the important issue of lasting stewardship and the particular requirements of new media art and takes the position that works should not be segregated by medium. This is a principled position. At the same time, Ippolito acknowledges that he is constrained, with such a policy, in what he can show and especially acquire because it must ‘succeed,’ which can affect [the] question of not knowing, necessarily, what such success might look like. (Dietz 2005)

Institutions are not able to keep/preserve/conserve/provide access to many variable media works - and in this definition, one must include analogue and digital works (and combinations of the two).

The initiatives investigated all work from the premise that documentation is crucial to a preservation solution. Some artworks are not meant to be kept in the traditional sense that you might keep a painting for example, but the documentations, algorithms and instructions or scores for variable media works at least preserve some of the creative content - the evidence that these works have existed in some point in space-time. These initiatives base their preservation policies on the idea that we must prevent losing the knowledge of how and why these works were created, performed, and installed[14].

The key to this preservation, which seems to now be emerging from the above mentioned initiatives, is to use methods and processes that artists already engage in – the documentation, scores, scripts, instructions and texts of artists. This project proposes that we now go further, to influence the development of methods for preservation of artworks that artists can participate in and use themselves.

top of page | homepage & table of contents | next section - chapter 2

Endnotes

[1] That Warhol owned two of Duchamp’s Boîte en Valises (Vesna 1999), raises some questions about Warhol’s artistic intent in the creation or accumulation of his Time Capsules (National Gallery of Victoria 2005). Many question whether Warhol created these Capsules as a specific collection or assemblage. Were they a random accumulation, a chronological narrative, or a series of mixed media journals in a box? Whatever his motivations, Warhol, and so many other artists in the last one hundred years, have been influenced by Duchamp, and continue to be influenced by him even now.

[2] Fluxus art is sometimes also known as “Intermedia”, a term coined by Dick Higgins.

[3] Mike Parr’s performance work often involved self mutilation: winding a fuse up his leg and setting light to it; or simulated self-mutilation as with the now infamous performance where Parr, (who only has a partial left arm), takes an axe and proceeds to chop up his prosthetic arm - the audience unaware that the arm is prosthetic and filled with meat and blood.

[4] The work of Lyndal Jones and ACW will be discussed further in Chapter 3 due to their involvement with this research project and their participation in the documentation of artwork with the Blackaeonium archival system.

[5] A post on the Empyre email list in 2007 contained a discussion about Second Life by Christy Dena and Patrick Lichty (Dena 2007). The post discusses the very practice of keeping content on a variety of social software systems, referred to in the discussion as “tiering”. Tiering is described as different points of entry into a work, specifically done with Second Life works by capturing images, video and chat and posting this material to other sites.

[6] Sondheim also has work held in collecting archives - at New York University's Fales Collection, and Ohio State University's Avant Writing Collection, in Columbus (Salt Publishing 2009). For more information, see the PhD research blog <http://www.blackaeonium.net/phdblog/> (text search for “Sondheim”) for documentation of email correspondence with Sondheim where he discusses various issues relating to the archiving of his work.

[7] Part of a series of email correspondence between Sondheim and Cianci, which can be viewed in its entirety in the PhD Research Blog (Search for “Sondheim” in the Text Search area) <http://www.blackaeonium.net/phdblog>.

[8]Part of an email posted to Netbehaviour by Alan Sondheim:

“Sugar - I'm really really upset by what has happened. You must have kept permissions open for building - Selavy Oh has screwed my installation with a grid and I can't video at this point. You did say I'd have it for the next few days for documenting - what happened? I tried returning some of the elements, but it's too much. I tried banning but have no permis- sion. The documentation was extremely important to me - Simon Biggs is/was writing on the piece, someone from a dance/tech group here was doing a documentary on it, and Foofwa was doing an interview with me about it - all for publication. I also have a graduate student, Wafa, from Tunisia, who was bringing her thesis advisor into the site on February 28th - the last date the piece was supposed to be stable; now that can't happen and that does affect her thesis and defense of it.

I have no idea what to do - I'm forwarding this to Gaz and Ian, two people I trust, who might have some idea.

I do recognize that ephemeral nature of everything on Second Life, but you did clearly say to me I'd have it to the end of February and I was acting on that.” (Sondheim 2009)

[9] The research for the YouTube Remix project was conducted by Eduardo Navas, with involvement from the Software Studies Initiative.

[10] two areas of contemporary art that have converged in many recent projects such as those by Navas and Mark Amerika

[12] There are many other articles by Sue McKemmish and Frank Upward that have formed a part of this research, mostly relating to the records continuum model and to specific developments in archival science in Australia such as the “series system”.

[13] In fact, an artwork has been created by artists Penelope Lee and Susan Hewitt in 2008 to represent the petition and commemorate 100 years of women’s right to vote in Victoria – which Eric Ketelaar also mentions in his article (Ketelaar 2012).

[14] From research project blog entry on 29/02/2012, titled “Collecting new media art: just like anything else, only different” (Cianci 2004)

top of page | homepage & table of contents | next section - chapter 2

this page produced by lisa cianci on her website www.blackaeonium.net

comments and queries to lisa's email address on scr.im (for humans only)

created 01/12/2011

last modified 30/07/2012